Part II: Technical Foundation

Medical Informatics: The Bridge Between Worlds

A recurring theme during the event was the unique role of Medical Informatics. Prof. Kalyani Addya (KCDH) described it simply but powerfully:

"Medical Informatics is the bridge between doctors and engineers."

In the current landscape, medical professionals and technical experts often speak "different languages." There is a fundamental language mismatch where the data scientist’s technical abstractions must be reconciled with the clinician’s grounded experience. KCDH provides the common ground where engineering expertise (Data Science, AI) meets clinical realities (Patient outcomes, diagnosis).

The Pillars of Transformation

The core vision is to provide the best possible healthcare to India's vast population through two broad technical pillars:

- Electronic Health Records (EHR): A system that captures the complete patient journey—from hospital entry to exit.

- Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS): Actively assisting clinicians with real-time data, follow-up tracking, and predictive analytics.

Breaking the "Islands of Care"

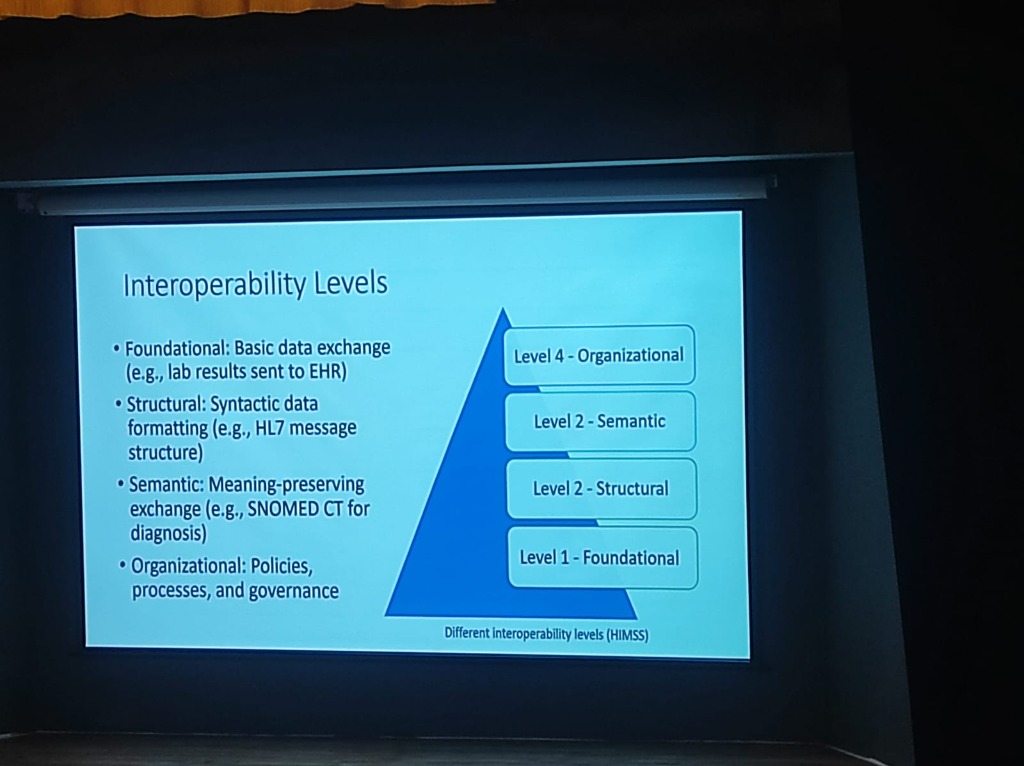

A major bottleneck is that healthcare systems often work in silos. To bridge these gaps, we must understand the Levels of Interoperability (as defined by HIMSS):

- Level 1: Foundational: Establishing basic data exchange (e.g., lab results sent to an EHR).

- Level 2: Structural: Ensuring syntactic data formatting (e.g., HL7 message structures) so data is in a readable format.

- Level 3: Semantic: Preserving meaning during exchange. Standards like SNOMED CT ensure that "CVA" in one system is understood as "Stroke" in another.

-

Level 4: Organizational: Encompassing the policies, processes, and governance that enable coordinated care across different legal and social entities.

-

The Intent Problem: Interoperability is often more of an "intent" problem than a technical one. A major cultural shift required is moving from institutional competition to a spirit of Collaboration.

The Path to Semantic Interoperability

-

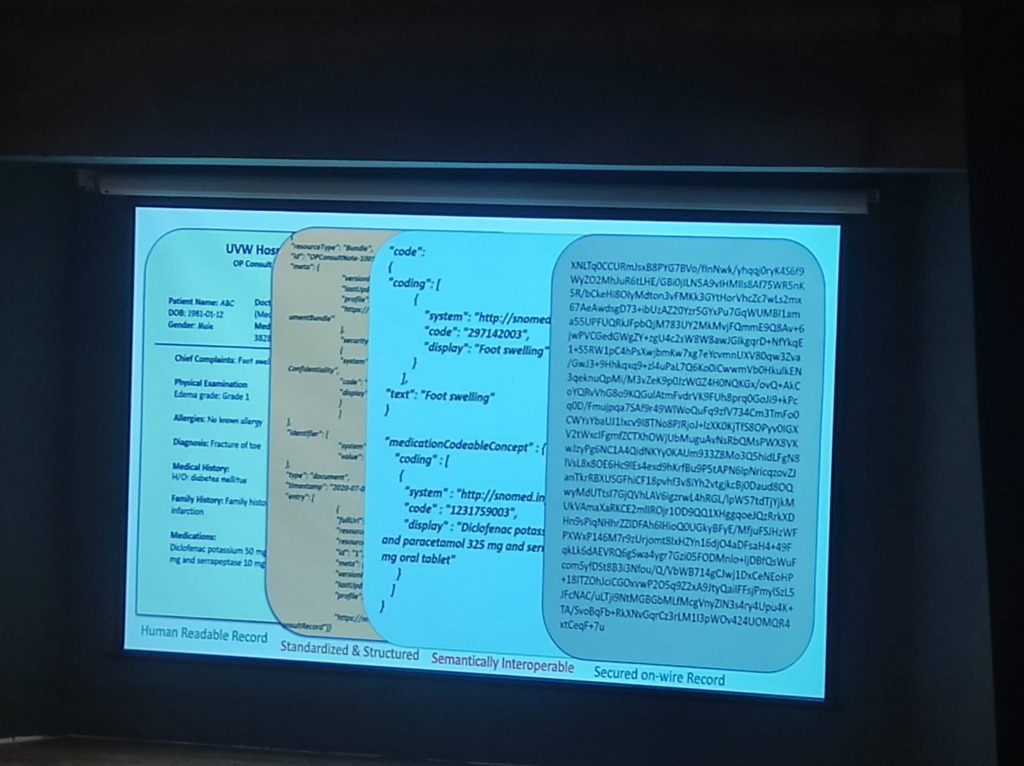

The Data Journey: From Text to Trust: Bridging the gap requires a rigorous transformation of medical data:

- Human Readable Record: The raw clinical input (e.g., "EDEMA grade 1", "Diclofenac Potassium 50mg").

- Standardized & Structured: Formatting the data into machine-level bundles (JSON/XML).

- Semantically Interoperable: Mapping terms to global standards like SNOMED CT (e.g., Code "297142003" for Foot swelling).

- Secured on-wire Record: Applying encryption to ensure data is protected as it moves across the network.

-

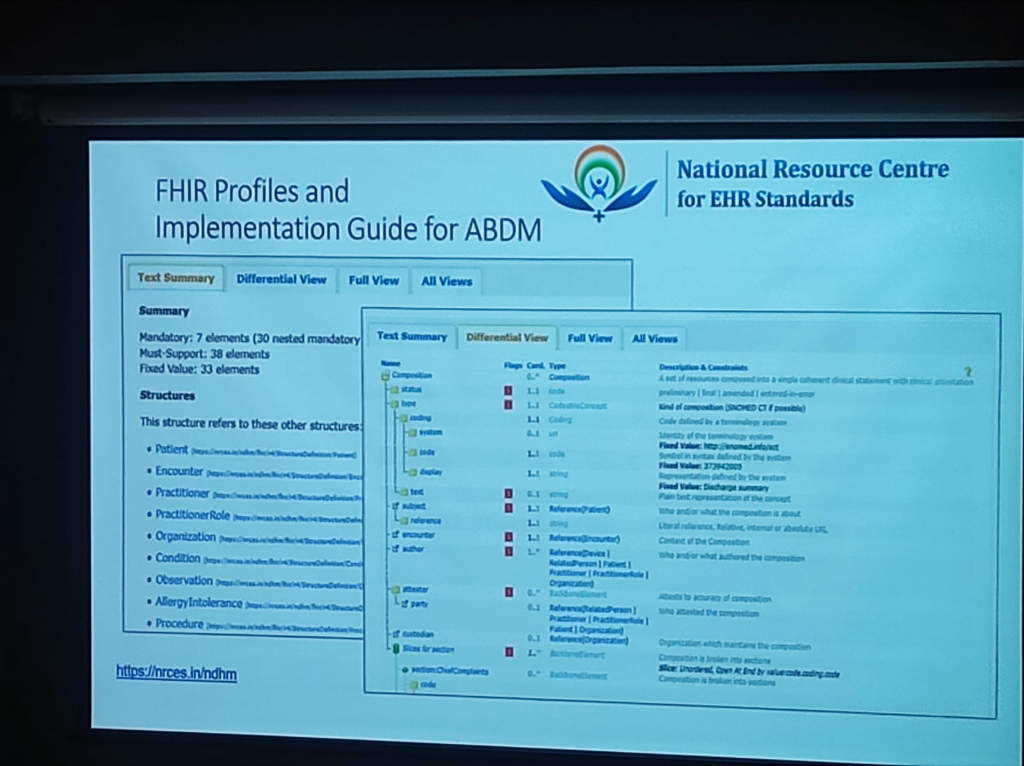

FHIR: The Blueprint for Exchange: FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) is the global standard developed by HL7 International that enables this exchange. Crucially, the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) uses FHIR as its primary data structure for creating India's unified health infrastructure.

-

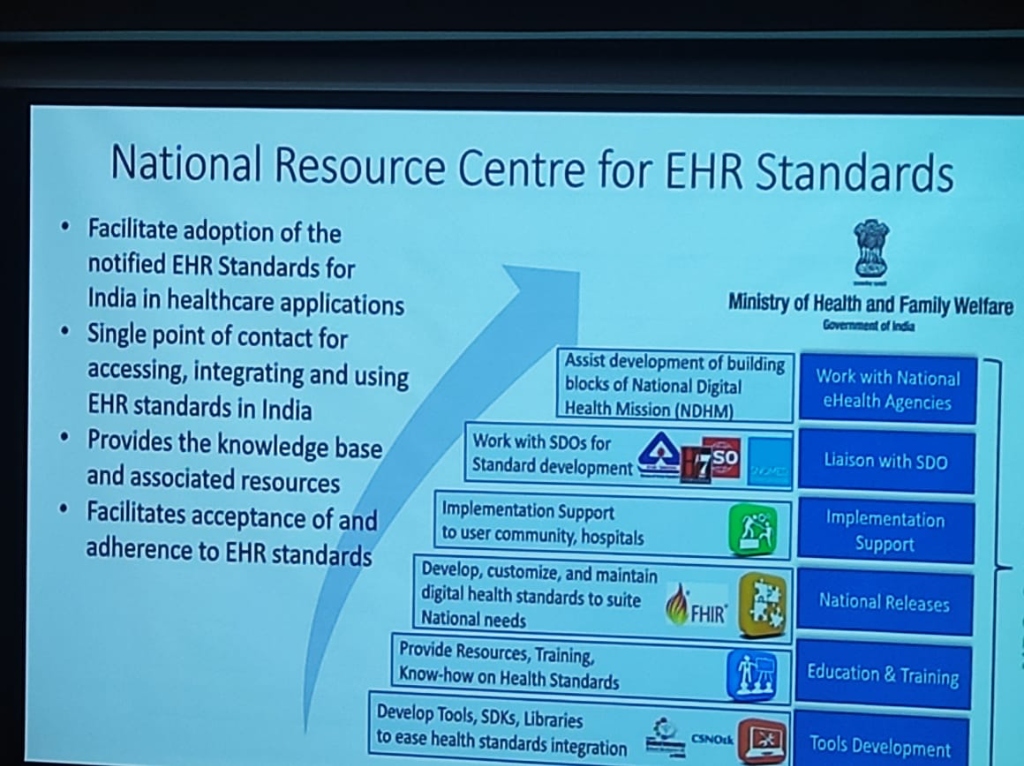

NRCeS Stewardship: As detailed by Ms. Manisha Mantri (NRCeS), the National Resource Centre for EHR Standards (NRCeS) maintains the FHIR Profiles and Implementation Guides tailored for ABDM.

- Comprehensive Specs: Combining a data dictionary, discrete objects/structures, and value tables for terminology.

- Modular Resources: Providing over 145 standard structures covering Healthcare Entities (Patient, Practitioner), Clinical Information (Condition, Procedure), and Financial Information (Claims, Invoice).

-

Reusable & Extensible: FHIR is designed to be customized for specific use cases through extensible Profiles.

-

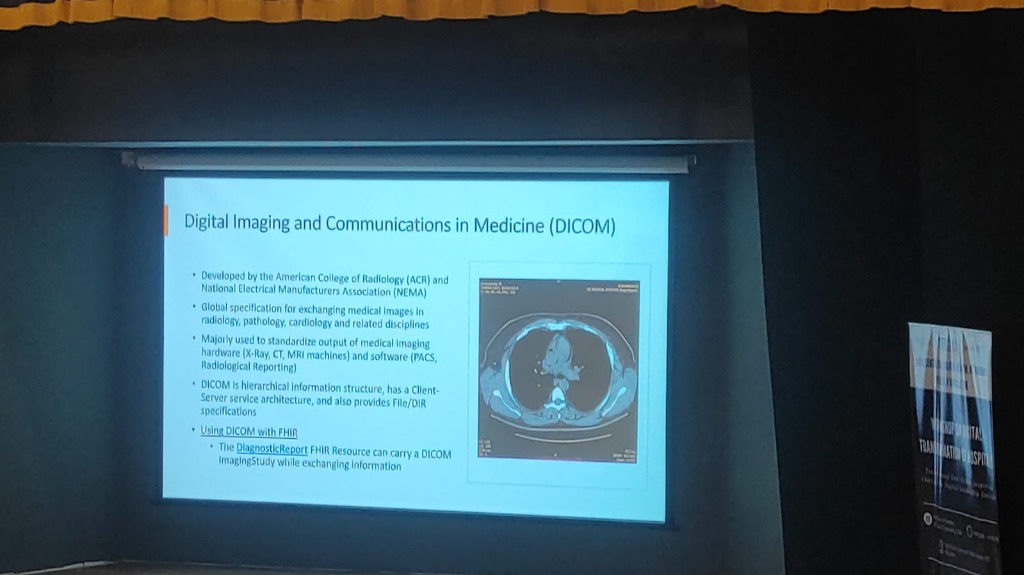

DICOM: Decoding Medical Imaging: While FHIR handles the clinical and administrative data, DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) is the global specification for exchanging medical images.

- Unified Imaging: Standardizing output from hardware like X-Ray, CT, and MRI machines to ensure seamless communication with PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication Systems).

- Clinical Inference through Metadata: Capturing critical attributes like laterality (left vs. right) and modality (CT vs. MRI), which are foundational for building advanced clinical inference models.

- DICOM & FHIR Synergy: The two standards work in tandem; for example, a FHIR DiagnosticReport resource can reference a DICOM ImagingStudy while exchanging information.

-

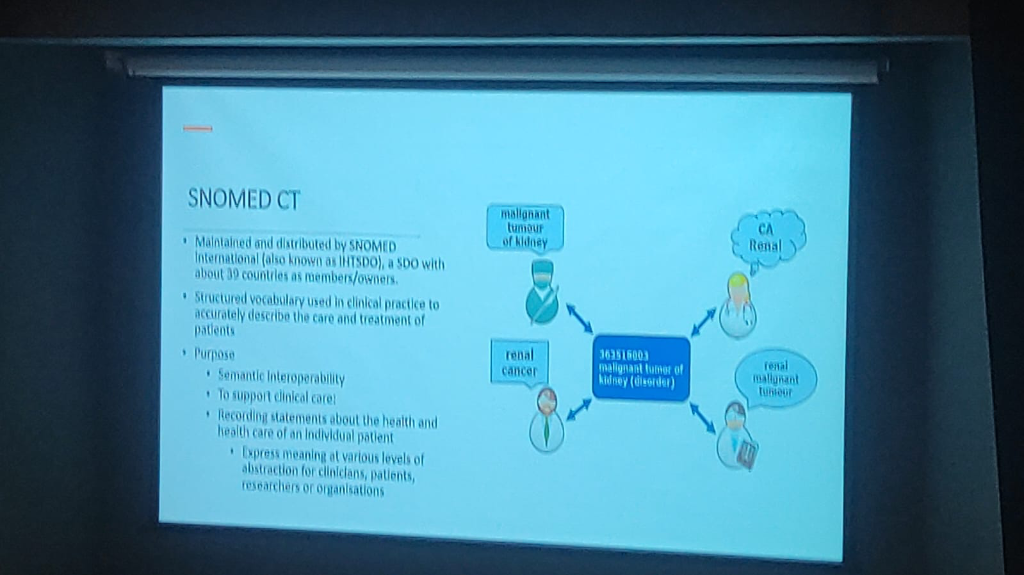

SNOMED CT: The Clinical Vocabulary: While DICOM captures the pixels and FHIR captures the structure, SNOMED CT provides the meaning.

- Unified Meaning: Providing a structured vocabulary that accurately describes clinical care—for example, resolving terms like "Renal Cancer" and "Malignant tumor of kidney" to a single code (363516003).

- Automated Semantic Mapping: Enabling SNOMED CT and ICD to be mapped automatically, allowing clinicians to document with clinical precision while administrative requirements are handled in the background.

- Semantic Interoperability: Ensuring that data remains consistent and understandable across different systems, clinicians, and researchers.

- Multidimensional Abstraction: Expressing clinical meaning at various levels to support both precise detail and high-level population health analysis.

-

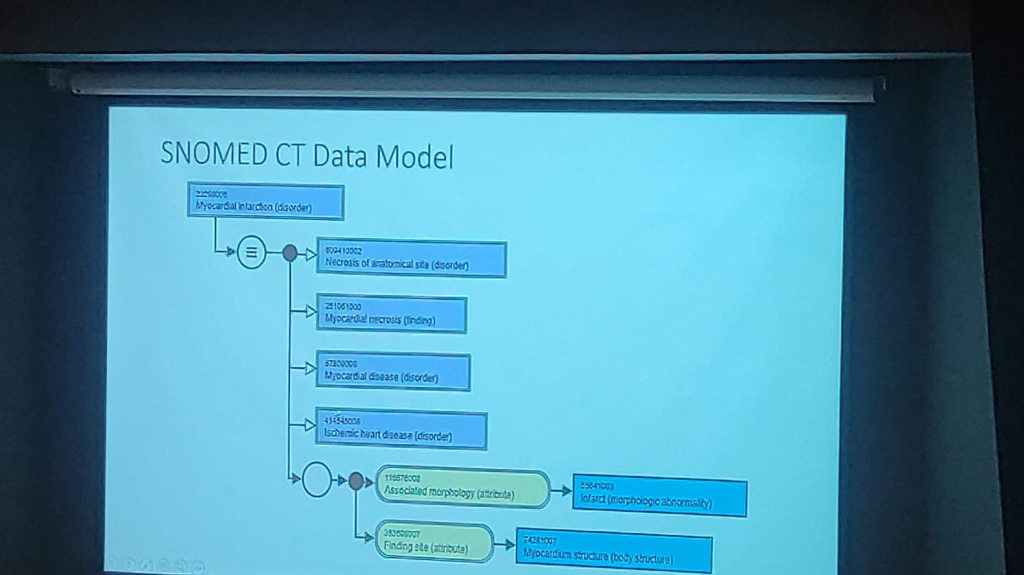

Advanced Analytics through the SNOMED CT Data Model: Beyond simple terminology, SNOMED CT provides a robust Data Model that simplifies complex clinical analytics.

- Relationship Mapping: The model enables associated disease analysis by linking concepts through specific attributes like Associated Morphology (e.g., Infarct) and Finding Site (e.g., Myocardium structure).

- Automated Inference: By structuring clinical data into logical hierarchies (e.g., Myocardial infarction → Necrosis of anatomical site → Myocardial necrosis), it allows for automated inference and more accurate epidemiological research.

- Data Consistency: This machine-level data model ensures that data points from diverse sources can be aggregated and analyzed without manual normalization, making large-scale clinical trials and public health surveillance far more efficient.

The "Standard Trinity": A Unified Foundation

The true power of digital health is realized when DICOM, FHIR, and SNOMED CT are integrated:

- Imaging (DICOM) provides the visual evidence.

- Exchange (FHIR) provides the structural pipe.

-

Vocabulary (SNOMED CT) provides the semantic clarity. Together, they ensure that a patient's health record is not just digital, but semantically rich, longitudinal, and universally understandable.

-

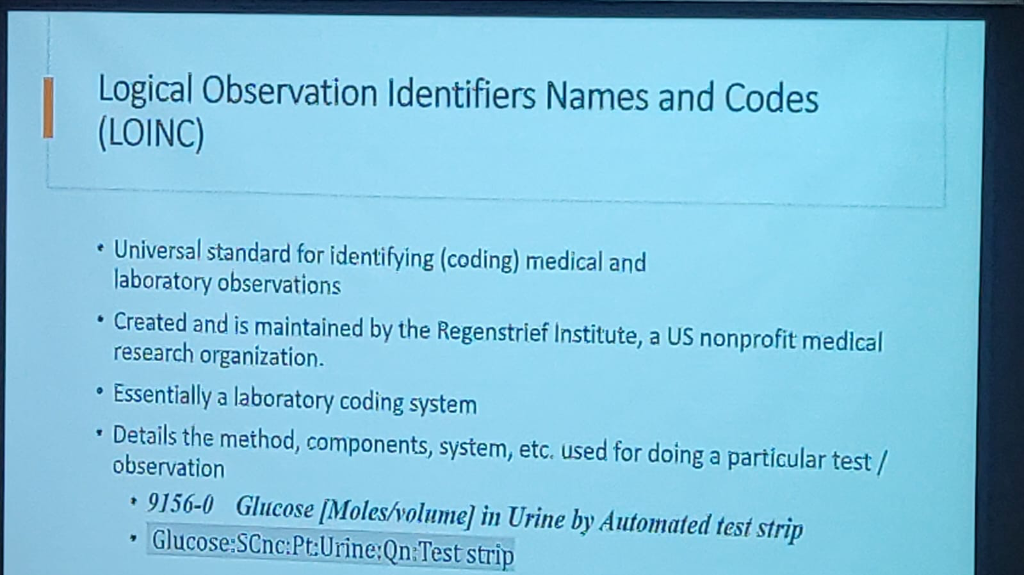

LOINC: Standardizing Lab Observations: While SNOMED CT handles clinical findings, LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes) is the universal standard for identifying medical and laboratory observations.

- Laboratory Precision: It details the exact method, components, and systems used for a particular test (e.g., Code 9156-0 for Glucose in Urine by automated test strip).

- Universal Coding: LOINC ensures that a "Glucose" test from one lab is understood identically by any other system, regardless of the local equipment used.

-

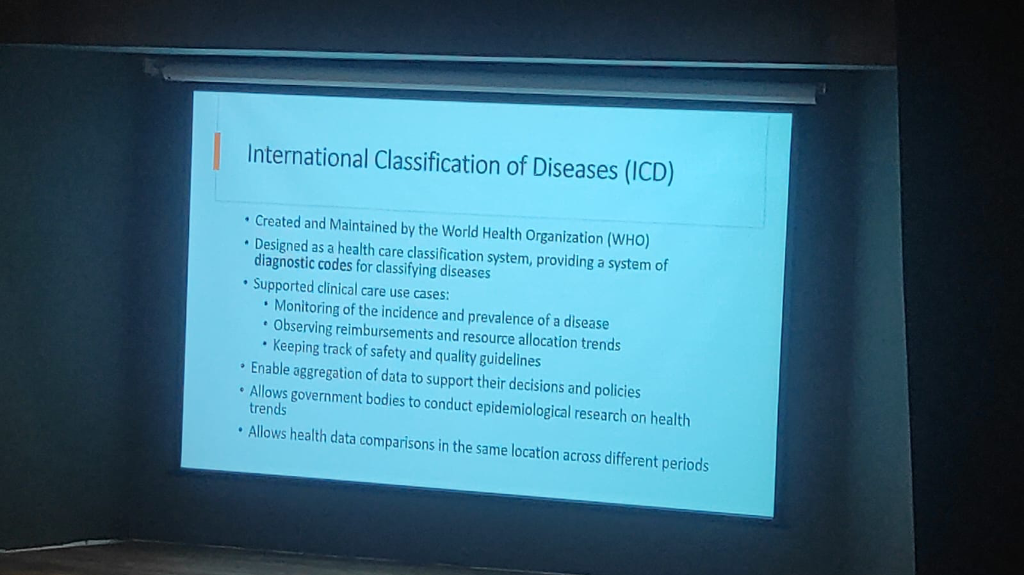

ICD: Disease Classification & Reporting: Maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO), ICD (International Classification of Diseases) is the global standard for health data, clinical documentation, and aggregation.

- Public Health Mandate: ICD codes are mandated for monitoring the incidence and prevalence of communicable diseases and for accurate mortality reporting.

- Epidemiological Insights: It allows government bodies to conduct epidemiological research on health trends and compare data across different periods and locations.

-

Common Identifiers (ABHA): National standards like ABHA serve as the common thread, bridging fragmented hospital numbers (MRNs) to ensure patient records are longitudinal and accurate.

- The SOP Gap: Digitization must focus on SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures), which are currently lacking across the board.

- The Build vs. Buy Dilemma: A core strategic question for any institution is whether to build from scratch (custom design and development), buy COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) applications, or adopt a hybrid approach of buying and customizing.

- Phased Implementation: To minimize "teething problems," adoption must be phased and well-planned rather than a "big bang" rollout.

Interoperability: The Technical Foundation

A key technical pillar discussed by Dr. Prabhu is the role of standardized interoperability through the National Resource Centre for EHR Standards (NRCES) and CDAC.

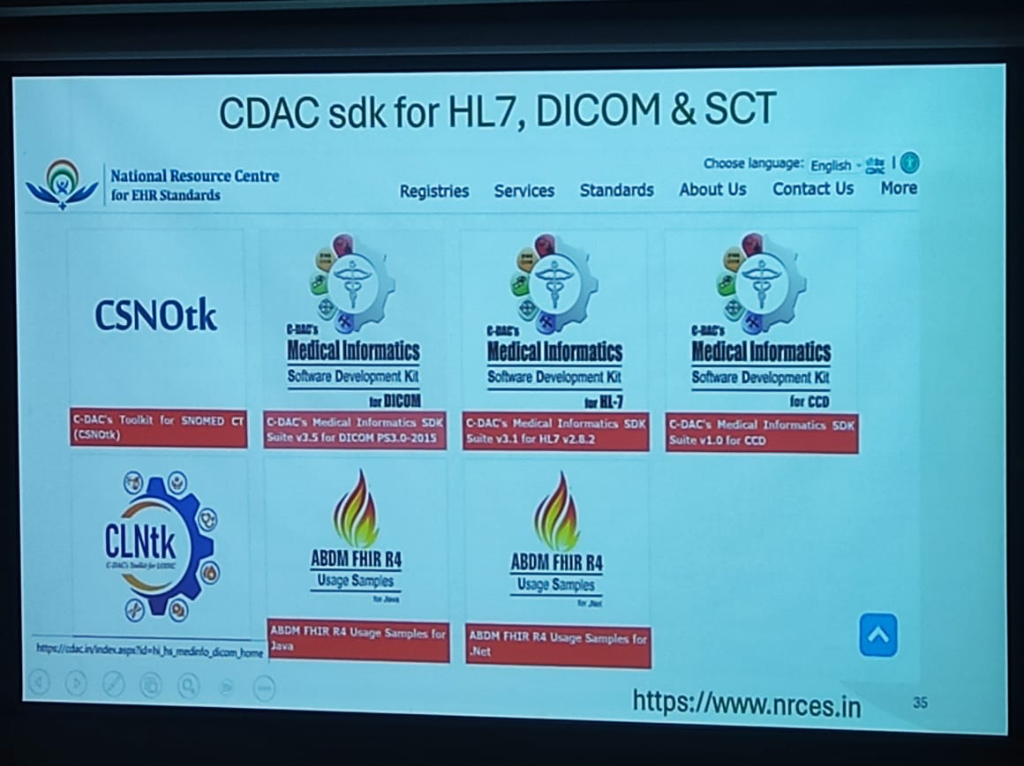

Figure: The CDAC Medical Informatics SDK Suite for HL7, DICOM, and SNOMED CT.

Figure: The CDAC Medical Informatics SDK Suite for HL7, DICOM, and SNOMED CT.

To achieve seamless data exchange across the national health ecosystem, a suite of standardized toolkits has been made available to developers:

- CSNOtk: C-DAC's Toolkit for SNOMED CT, enabling standardized clinical terminology across all electronic records.

- Medical Informatics SDK Suite:

- DICOM PS3.0-2015: For standardized medical imaging and communication.

- HL7 v2.8.2: The benchmark for electronic health information exchange.

- CCD (v1.0): For Continuity of Care Documents.

- ABDM FHIR R4 Usage Samples: To accelerate integration with the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission, official usage samples are provided for both Java and .Net environments.

- CLNtk: C-DAC's Toolkit for LOINC, standardizing laboratory and clinical observations.

These tools, hosted at www.nrces.in, provide the necessary "Lego blocks" for startups and established players to build ABDM-compliant healthcare applications.

OHDSI: Standardizing Global Evidence

A cornerstone of the clinical research roadmap is the adoption of OHDSI (Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics).

- From OMOP to OHDSI: The journey began with the OMOP (Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership), which has now morphed into the international OHDSI (Odyssey) organization.

- Real-World Evidence: OHDSI provides the open-source tools and standardized data models (OMOP Common Data Model) necessary to generate reliable evidence from observational health data across different institutions.

- The OHDSI India Chapter: Recently established (2 years old), this chapter is already collaborating on high-level policy questions from the Government and the WHO—for instance, studying the long-term effects of specific drugs on population health metrics like tuberculosis.

- Predictive Acute Care (Case Study: Cohere-med.com): One of the most compelling examples shared was Cohere-med.com, a startup focused on ICU automation. By utilizing high-fidelity EMR data, Cohere-med.com can predict the onset of Sepsis before it occurs. Sepsis is a condition that kills 60% of ICU patients, and early prediction using digital blueprints is a literal life-saver.

- The Data Payers: Ensuring Sustainability: A critical realization for startups is identifying who pays for these insights. While hospitals are the custodians, the Insurance, Pharma, and MedTech industries are the primary "payers" for high-quality, anonymized clinical data. This insurance-led model ensures the financial sustainability of the digital mission.

- The Triple Bottom Line: Innovators are encouraged to "do well" (build successful products), "solve the country's problems," and "make some money" on the side.

- The Support Ecosystem: The synergy between academic hubs like IIT Bombay (KCDH) and national mission teams creates a blueprint for how technical excellence and public policy can collaborate to support this new wave of health-tech entrepreneurship.

Finalizing National Standards: The NRC Hub

A critical role of the NRC (National Resource Centre for EHR Standards) is finalizing and pushing the HL7 FHIR R4 standards to the country. This ensures that every digital health application in the ecosystem speaks the same semantic language.

The Big Tech Paradox: The Apple Case

- The Compliance Question: A common question in digital health circles is why global giants like Apple are not ABDM compliant.

- The Standards Gap: While Apple Health provides a sophisticated personal health record platform, it does not currently adhere to the mandatory HL7 FHIR R4 profiles finalized by the NRC for India.

- Proprietary vs. Open: Big Tech's reliance on proprietary data models creates a friction point with national missions that mandate open, interoperable standards for public-private data exchange.

The 7 Core Care Contexts

To ensure granular linkage of clinical encounters, the ABDM framework utilizes Care Contexts. Currently, there are 7 available care contexts that systems must map to:

- OPD Consultation: For standard outpatient visits.

- IPD Admission: For inpatient stays and procedures.

- Diagnostic Test: For lab and imaging results.

- Immunization: For vaccination events.

- Prescription: For digital medication orders.

- Wellness/Health Record: For wearable and telemetry data.

- Pharmacy Invoice: For proof of medication purchase.

The Unique ABHA Constraint: One Person, One ID

A fundamental architectural rule of the national mission is the Uniqueness of the ABHA Number. - No Multiplicity: It is not possible for a single individual to have multiple ABHA numbers. The ID is a unique, life-long identifier anchored to a person's identity. - Single Version of Truth: This constraint ensures that clinical records from fragmented visits are correctly routed back to the same longitudinal history, preventing data silos or duplicate profiles.

Mandatory FHIR R4: The Integration Baseline

For any HIS or EMR to interact with the national HIE, it must undergo a specific type of integration.

- Strict Compliance: ABDM, in collaboration with NRCeS, has mandated HL7 FHIR R4 as the only acceptable standard for data exchange.

- Resource Definition: Whether it's a vaccine certificate or a pharmacy invoice, every HI type is modeled as a FHIR resource (e.g., Patient, Observation, DiagnosticReport), ensuring that data is self-describing and semantically rich.

DPDP Act and the Right to Forget: Consent Governance

The newly enacted Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act introduces a fundamental shift in patient agency:

- Consent Autonomy: Consent is now recognized as a non-negotiable right. A patient can withdraw consent at any point in time, effectively opting out of the discovery layer for specific longitudinal records.

- The Medico-legal Dilemma: This autonomy raises complex questions for medico-legal cases. If a patient withdraws consent for a record that is critical to an ongoing legal proceeding, the ecosystem must navigate the friction between individual privacy rights and the judicial requirement for evidence.

- Patient Awareness & Empowerment: The current focus of the mission is shifting toward large-scale Patient Education. The goal is an ecosystem where every citizen understands their rights under the DPDP Act and the benefits of maintaining a secure, linked health history.

The Implementation Frontier: HIE & Operational Realities

Bridging the gap between a "digital vision" and "operational reality" requires addressing the technical and governance frictions of a national Health Information Exchange (HIE).

The Standards Paradox (HL7 v3 vs v2.7)

Interoperability is often hampered by Versioning Conflict. While national missions advocate for modern standards (FHIR), most legacy hospital systems (LIS/RIS) still run on HL7 v2.x. - Data Integrity Risk: Forcing a match between HL7 v3 (XML) and HL7 v2.7 (Pipe-delimited) can lead to "semantic slippage," where critical clinical flags or lab nuances are lost during translation. - The Middleware Requirement: Successful HIE implementation requires robust Intermediate Mapping Layers that can handle these versioning mismatches without data loss.

OPD Success vs. The CDA Challenge

India has seen massive success in digitizing Out-patient (OPD) registration and summaries. However, the next frontier is the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA): - OPD (Snapshot): Success is driven by simple, structured summaries. - Inpatient (Narrative): Complex inpatient care requires a more robust CDA/CCR (Continuity of Care Record) framework to capture the longitudinal depth of a patient's stay, which remains a significant implementation hurdle for most hospitals.

Data Ownership vs. Digital Lockers

A common governance misunderstanding involves the "ownership" of medical data: - Ownership: The Hospital (the fiduciary) remains the owner and custodian of the primary clinical record. - The Locker (Locker/PHR): Platforms like the ABDM Health Locker are not owners; they are secure gateways designed to provide the patient with agency over their own health history.

International Benchmarking

India's federated approach draws parallels with global leaders, yet remains unique:

The Federated Edge: India's Unique Architecture

Unlike centralized models, India's HIE is designed as a Federated Architecture, ensuring that data stays at the source while allowing discovery and consent-based access at a national scale.

Privacy: An Ethical & Fiduciary Foundation

The push for digital health privacy is not merely a legal requirement; it is rooted in centuries of Medical Ethics and the unique nature of the clinical bond. Within this framework, Data Security is the means to achieve Privacy Rights—the technical foundation that makes individual agency possible.

Respect for Autonomy

A fundamental principle of medical ethics is the Respect for Autonomy. This gives patients the right to ensure that data pertaining to them is not accessed by anyone unless it is absolutely necessary for the specific service being provided. Privacy is the mechanism through which this autonomy is exercised in a digital system.

The doctor-patient relationship is fundamentally a Fiduciary Relationship—a bond built on trust, reciprocity, and an implicit promise of safety:

- Trust & Reciprocity: Patients share their most sensitive information with the faith that it will be used only for their benefit. In return, doctors rely on the truthfulness of that information to provide accurate care.

- The Confidence Mandate: Clinical interaction requires a level of confidentiality that prevents harm to the patient. Without explicit assurance from the healthcare ecosystem, patients will not willingly part with their sensitive health data.

DPDP: Substantiating Medical Values

The Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 should not be viewed as "reinventing the wheel." Instead, it is a regulatory framework that substantiates existing medical ethics with a better, more robust legal structure. It codifies the principles of confidentiality and no-harm that have always been the bedrock of healthcare.

Security & Compliance: The Global Mandate

The AIIMS hacking case serves as a stark reminder that simple firewalls are no longer enough. Security must be multi-layered, compliant with global standards, and rooted in the principle of Security by Design—where protection is an architectural requirement, not an afterthought. Governance now mandates a "Privacy-First" approach to how data is collected, processed, and shared.

Medical data is a global asset requiring adherence to rigorous regulatory frameworks:

- NABH (India): National Accreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers standards for operational and data quality, now featuring a progressive maturity framework for digital health.

- HIPAA (USA): While often perceived as the healthcare "gold standard," HIPAA compliance does not automatically satisfy local DPDP mandates. Indian hospitals must cater to specific local nuances and rights not covered by US legislation.

- GDPR (EU): The General Data Protection Regulation, providing stringent privacy requirements that served as a partial model for the DPDP Act.

- DPDP Act 2023 (India): The definitive, compulsory national legislation for data handling in India, mandating strict consent and introducing unique rights and heavy penalty liabilities. The rules are expected to be fully enacted by April 2026.

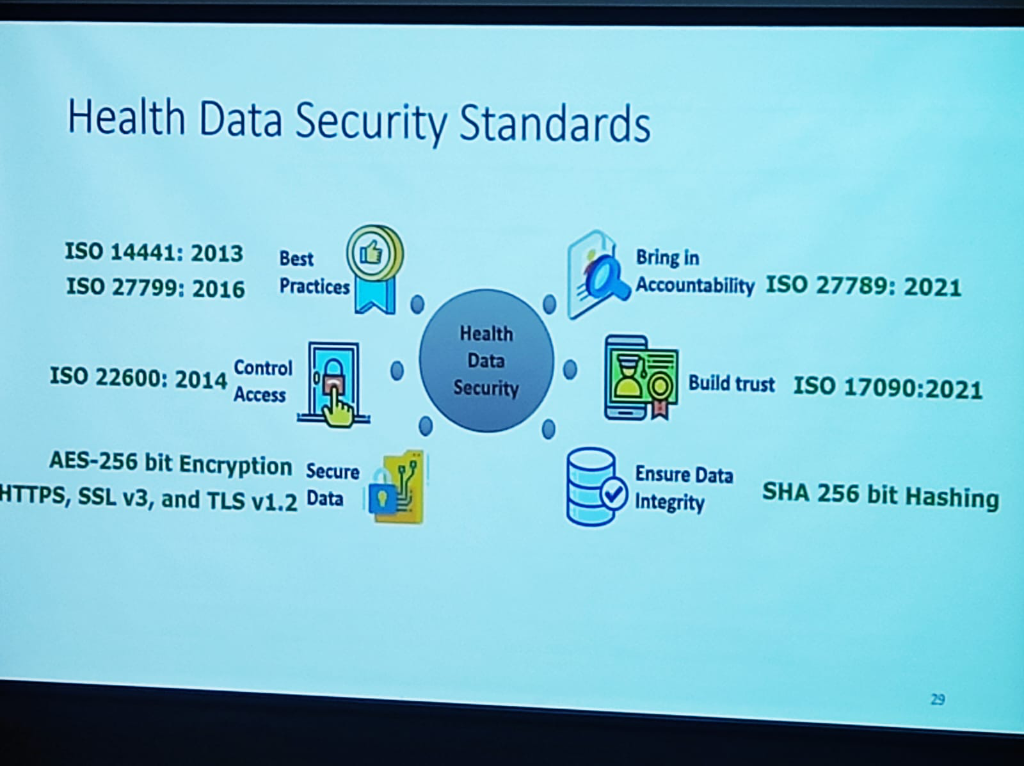

Security is not just a policy; it is built on a foundation of rigorous international standards that ensure Resilience and Trust:

- Robust Frameworks: Adherence to ISO 27001, 14441, 27799, 22600, 27789, and 17090 provides the global benchmark for health data security.

- Technical Safeguards: Implementing AES-256 bit Encryption for data on the wire and SHA-256 bit Hashing to ensure data integrity.

- Granular Security Policies: True security extends to human behavior. Institutions must enforce policies for Remote Work (secure protocols) and Clear Desk & Clear Screen (mandatory system locking) to prevent accidental data exposure.

- Operational Disruption: The DPDP Act is a workflow disruptor. Since every discrete data point in a hospital involves personal health information, compliance impacts every aspect of management—from front-desk registration to clinical discharge.

Beyond national legislation, clinical data governance is bolstered by a network of sectoral policies and ethical guidelines:

- IMC Regulations 2002: Directs the maintenance of medical records for specific retention timelines and mandates the computerization of records for quick and accurate retrieval.

- National Ethical Guidelines (Human Research): Establishes policies for data capture, acquisition, sharing, and ownership, emphasizing the role of Ethics Committees in safeguarding participant privacy.

- ART Act 2021: Specifically mandates that assisted reproductive technology clinics and banks protect all confidential information and maintain accurate, secure records.

- ICMR Lab Guidelines 2021: Defines rigorous standards for Good Clinical Laboratory Practices, focusing on multi-dimensional security (Hardware, Network, Application, Personnel) and mandatory Disaster Recovery planning.

A critical nuance in Indian digital health governance is the relationship between the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) and the DPDP Act:

- Voluntary vs. Compulsory: While ABDM participation is a voluntary framework for hospitals, the DPDP Act is a compulsory, legislative mandate.

- The HDMP Trigger: Once a hospital volunteers for the ABDM ecosystem, it automatically triggers the Health Data Management Policy (HDMP)—a sectoral regulation that mandates:

- Secure Storage: Ensuring digital health records are stored in encrypted, compliant environments.

- Rigorous Access Controls: Enforcing role-based access for every clinical interaction.

- Breach Reporting: Mandatory reporting systems for any security incident within the ABDM network.

- ABDM-Certified Tools: Hospitals are increasingly mandated to rely on ABDM-certified tools (EMRs, LIMS, Health Lockers) that have been vetted for these sectoral security standards.

Regulatory Risk: The "Dual Penalty" Threat

Non-compliance in a digitized environment carries a double-edged risk. A data breach doesn't just trigger one investigation; it triggers two: 1. Sectoral Penalty: Penalties and blacklisting under the ABDM/National Health Authority (NHA) framework for violating the Health Data Management Policy. 2. National Penalty: Massive financial penalties (up to ₹250 Crores) under the DPDP Act 2023 for failure to protect personal data. This dual-track liability makes investment in robust cybersecurity not just an IT goal, but a core strategy for institutional survival.

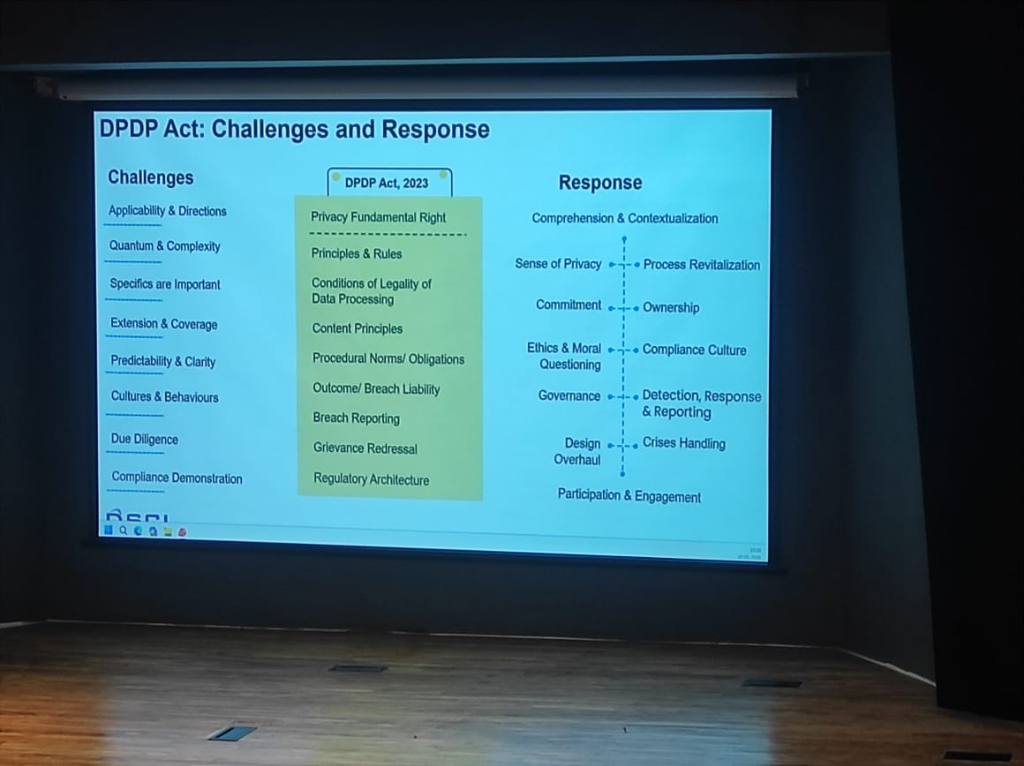

The implementation of the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 represents a monumental shift for Indian healthcare. As Bagmishka Puhan (Associate Partner, TMT & Digital Health Legal) details, privacy is no longer an option; it is a Fundamental Right.

The High Stakes of Compliance The Act introduces a regime of Heavy Penalties specifically targeting Breach Liability. Hospitals must now navigate substantial procedural norms, from Breach Reporting and Grievance Redressal to maintaining a robust Regulatory Architecture.

Core Challenges for Hospitals:

- Personal Data & Scanned Documents: Under DPDP, "Personal Data" is any identifier that can pinpoint an individual, either by itself or in conjunction with other data sets. Crucially, the Act applies to data collected in digital form or collected in non-digital form and digitized subsequently (the "Scanned Document" rule).

- Unique Indian Rights: The Act introduces rights that do not exist in traditional global legislation (like HIPAA or GDPR), requiring institutions to build specific technical interfaces for:

- Right to Nominate: The ability for a patient to nominate a person who will exercise their rights in case of their disability or death.

- Right to Grievance Redressal: A mandatory, institutionalized mechanism for addressing user complaints.

The Patient's Charter: Rights of the Data Principal

Under the DPDP Act, patients (Data Principals) are granted a comprehensive charter of rights designed to restore their agency over their health data:

- Right to Access & Control: Patients can request information about their personal data and obtain a summary of data processed.

- Right to Correction & Erasure: The right to update inaccurate data and request the deletion of data once the purpose is served.

- Right to be Informed: Beyond just data, patients have the right to be given information about tests, treatment options, and their associated benefits and risks.

- Right to Informed Choice: The mandate to make an informed choice and provide explicit Informed Consent before processing begins.

- Right to Safety & Security: The right to expect providers to keep health information safe and secure at all times.

- Unique Indian Mandates: The Right to Nominate (for disability or death) and the Right to seek treatment from a registered medical practitioner (noting the mandatory requirement of identification).

- Applicability & Directions: Understanding the specific legal directions for various healthcare departments.

- Quantum & Complexity: Managing the massive volume and diversity of health data under strict procedural obligations.

- Due Diligence & Compliance Demonstration: The burden of proof is on the institution—hospitals must proactively demonstrate they have secured patient data.

Data Protection: Clinical Best Practices

Implementing a resilient privacy framework requires moving from policy to practice. The following 8-pillar framework defines the gold standard for clinical data protection:

- Strict Data Minimization: Collect and process only as much data as is strictly necessary for the therapeutic purpose.

- Recorded Consent: Ensure that every piece of patient data is backed by recorded, unbundled consent.

- Need-to-Know Access: Restrict access to patient files only to users who have a legitimate clinical or administrative requirement.

- Lifecycle Security: Ensure data is secure at all points of interaction—from capture to archive.

- User-Driven Accuracy: Allow patients to update or verify their information, ensuring clinical record integrity.

- Statutory Retention: Retain data only as long as required by law or for the legitimate purpose for which it was collected.

- Timely Deletion: Permanently delete personal data when there is no further clinical or legal need for its retention.

- Accountability & Auditing: Maintain logs and conduct regular audits to ensure the entire lifecycle of the data is accounted for.

- Annual Governance Audits: Conduct a mandatory annual audit specifically targeting Data Deletion, Retention policies, and Purging schedules to ensure technical execution matches clinical and legal mandates.

The Transformation Path (Response Strategy): To survive this regulatory shift, institutions must move from simple awareness to active participation:

- Comprehensive Contextualization: Mapping DPDP principles to specific clinical workflows.

- From Commitment to Ownership: Shifting accountability from a single "IT person" to clinical and quality leads.

- From Ethics to Compliance Culture: Building a moral consensus across the hospital that prioritizes Privacy by Design.

- Detection, Response & Reporting: Moving from passive governance to active Crisis Handling and automated breach detection.

Figure: The strategic roadmap for DPDP Act implementation—transforming institutional culture from passive compliance to active crisis handling.

Figure: The strategic roadmap for DPDP Act implementation—transforming institutional culture from passive compliance to active crisis handling.

Transparency: The Notice & Consent Standard

At the heart of DPDP is a new benchmark for transparency. Institutions must move beyond "fine print" to active disclosure:

-

The Transparency Notice: Hospitals must explicitly inform patients:

- What kind of information is being collected.

- How the information is going to be processed.

- Who all the information is being shared with (Third-party TPAs, Medtech, etc.).

- Why: The specific purpose for which the data is required for service provision.

-

Valid Consent: Consent is no longer a "pre-ticked box." For consent to be valid under DPDP, it must be:

-

Clear, Unambiguous, and Unbundled: It must be a specific, stand-alone permission, not tucked into a general "Terms and Conditions" document.

- Informed Participation: In setups like Teleconsultation, patients must be briefed on the shortcomings and limitations of the platform before their data is processed.

The DPO & The Cultural Shift

A critical component of this legal architecture is the Data Protection Officer (DPO). However, the role faces unique challenges in the Indian context:

- The Query Gap: Currently, DPO-related questions and scrutiny are significantly more mature and frequent outside India. International users and regulators demand more granular data handling details than domestic entities.

- Social Economy & Culture: Privacy governance in India is deeply influenced by our unique social economy and culture. Unlike Western-centric models, Indian privacy must account for a transition from a community-based data sharing culture to a strictly regulated individual rights model.

- From Paper to Practice: Compliance is shifting from "filling forms" to managing real-time data rights. This requires a cultural shift where the DPO is not just a legal signatory but a core part of the hospital's clinical and digital workflow.

Governance & The "CSO Gap"

As Vinayak Godse (CEO, Data Security Council of India - DSCI) emphasizes, the cybersecurity landscape in healthcare is significantly behind other regulated sectors.

- The CSO Absence: Unlike the financial sector, where the Chief Security Officer (CSO) is a mandatory and institutionalized function, most Indian hospitals lack a dedicated leadership role for cybersecurity. Security is often treated as an "IT side-task" rather than a core governance pillar.

- The Banking Comparison: In banking, the RBI has established a rigorous framework that mandates security posture, response protocols, and continuous auditing. Healthcare requires a similar shift from passive protection to active, regulated cybersecurity governance.

- Fragmented Infrastructure Risks: The "fragmented" nature of hospital infrastructure—from legacy on-prem servers to unmanaged medical devices—creates significant data protection gaps and increases vulnerability to ransomware.

- Continuous Posture Improvement: Post-AIIMS, the message is clear: security is not a "fire-and-forget" solution. It requires a continuous improvement of architecture, posture, and response capabilities to stay resilient against evolving threats.

The Evolution of Security Governance

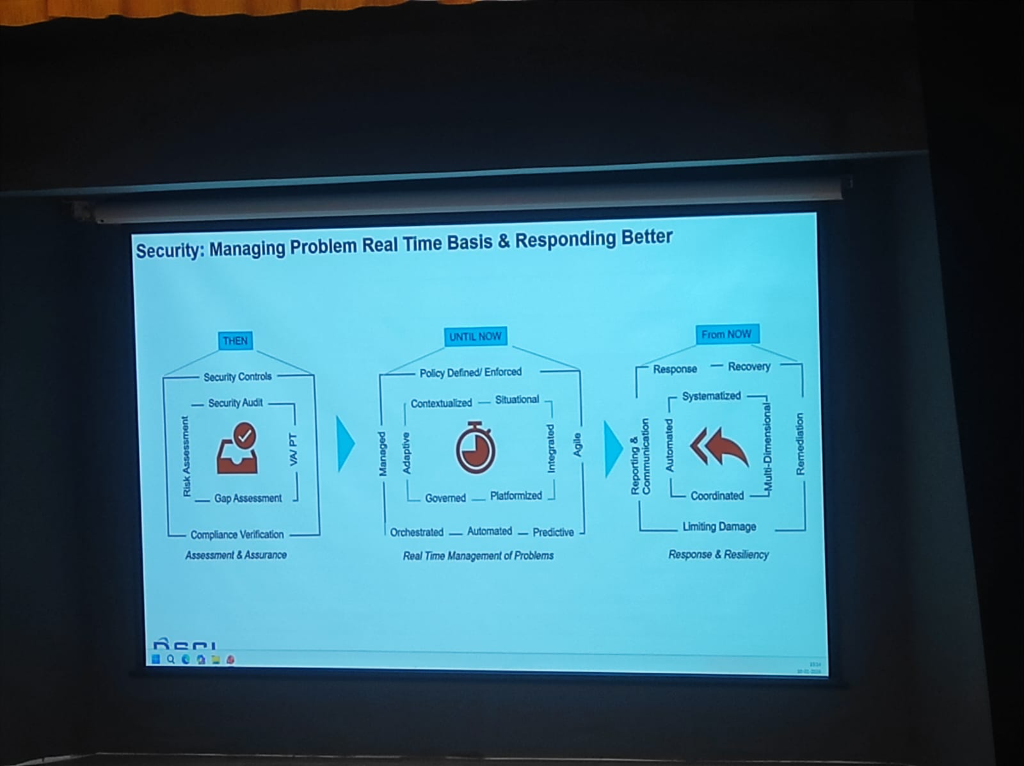

The strategy for protecting medical data has undergone a fundamental shift. As DSCI outlines, the journey moves from passive assurance to active resiliency:

- THEN (Assessment & Assurance): Focus on static Security Controls, Audits, Risk Assessments, and Compliance Verification.

- UNTIL NOW (Real-Time Management): Shift toward Policy Enforcement, Orchestrated and Automated responses, and Predictive situational awareness.

- FROM NOW (Response & Resiliency): The future is Multi-Dimensional Resiliency. This involves Systematized Response and Recovery, Automated Remediation, and Coordinated Communication to limit damage in real-time.

Figure: The paradigm shift in security governance—from audit-based compliance to multi-dimensional clinical resiliency.

Figure: The paradigm shift in security governance—from audit-based compliance to multi-dimensional clinical resiliency.