Part IV: Agentic Frontier & AI

Academic Perspectives: AI, Statistics, and Wearables

Beyond technical standards, the event highlighted the academic and research-driven foundation of KCDH, bridging the gap between clinical needs and data science:

- The Collaboration Paradigm (Prof. Kshitij Jadhav): Emphasized that AI development must be a Clinical-Data Scientist action plan. Clinicians shouldn't just be "providers of data" but active co-pilots in defining the "Why" of AI.

- The Mathematical Foundation (Prof. Saket Choudhary): Highlighted that Statistics are the Grammar of AI. For data-driven healthcare to be trustworthy, it must be grounded in mathematical rigor and address the inherent stochastic nature of biological data.

- Wearable Intelligence (Prof. Nirmal Punjabi): Detailed the journey of Translating Wearable Intelligence into Actionable EHR Data. Wearables are no longer just "fitness trackers" but critical sources of continuous physiological data that must be semantically linked to the patient's longitudinal record to drive predictive care.

AI Governance: Standard Adoption First

As hospitals look toward the future, the role of AI Governance and Ethical Usage becomes paramount.

- A Prerequisite, Not an Afterthought: Standards are an integral part of AI. While NABH and other bodies are yet to adopt specific AI-only standards, the adoption of data standards is the most critical prerequisite for ethical AI deployment.

- The AI Regulatory Choice: NABH has made a deliberate strategic decision to steer clear of AI standards in the current national framework. The priority is to ensure foundational data integrity, human accountability, and patient safety first, before mandating AI-specific regulatory norms.

- Fragmented Data Barrier: Fragmented, non-standardized data hinders the true potential of AI. Universal adherence to NABH digital standards is the key to unlocking clinical quality at scale.

Agentic AI: The Orchestration Frontier

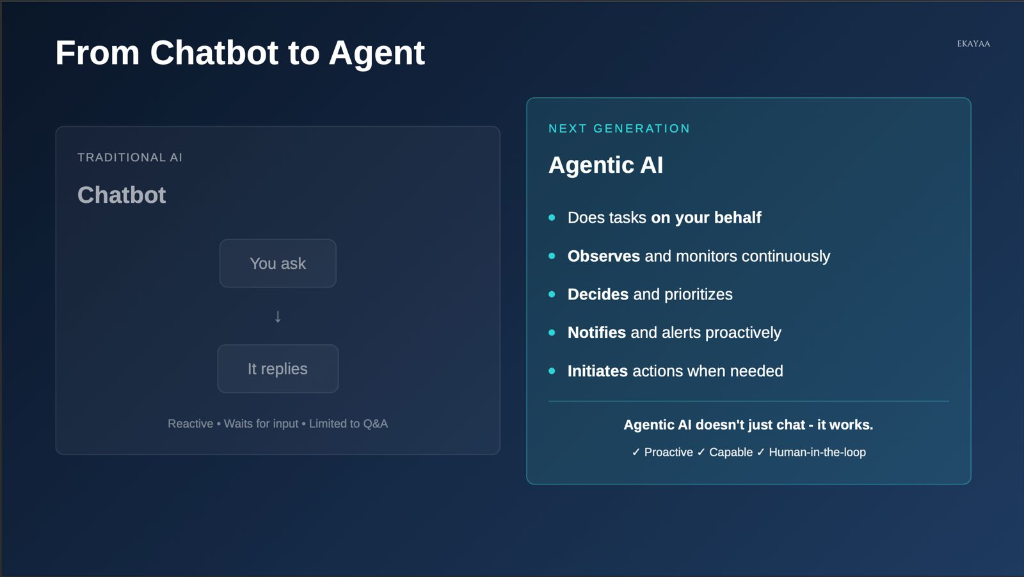

The future of digital health is moving beyond simple data entry and retrieval. We are entering the era of Agentic AI—systems that don't just reply, but work and coordinate.

From Chatbots to Clinical Agents

Traditional AI (Chatbots) is reactive and limited to Q&A. Agentic AI is a proactive partner that observes, decides, and initiates actions on your behalf.

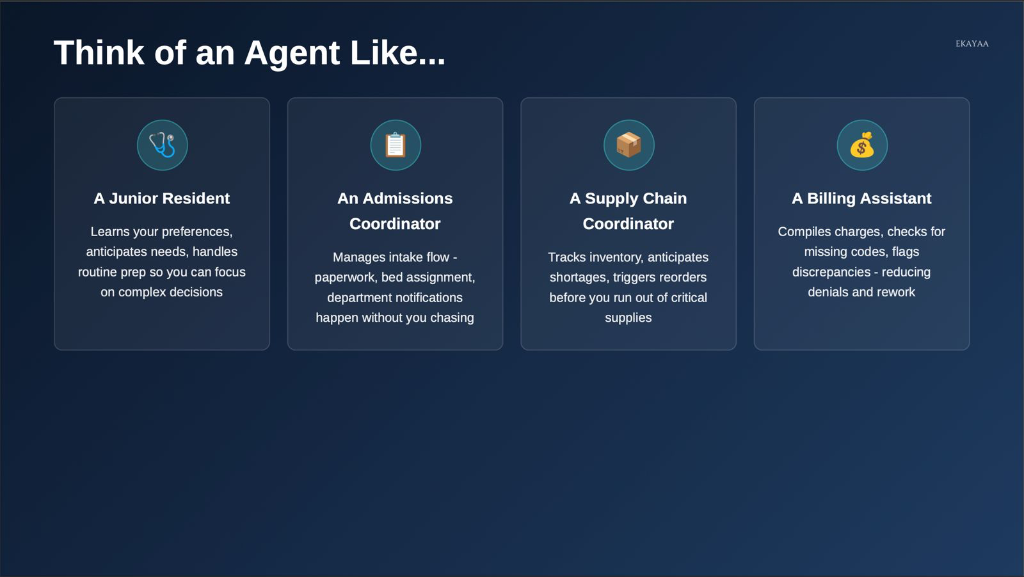

Agents as Digital Resident Coordinators

Think of an Agent not as a piece of software, but as a specialized digital coordinator—a Junior Resident, an Admissions Coordinator, or a Billing Assistant—that learns preferences and anticipates needs.

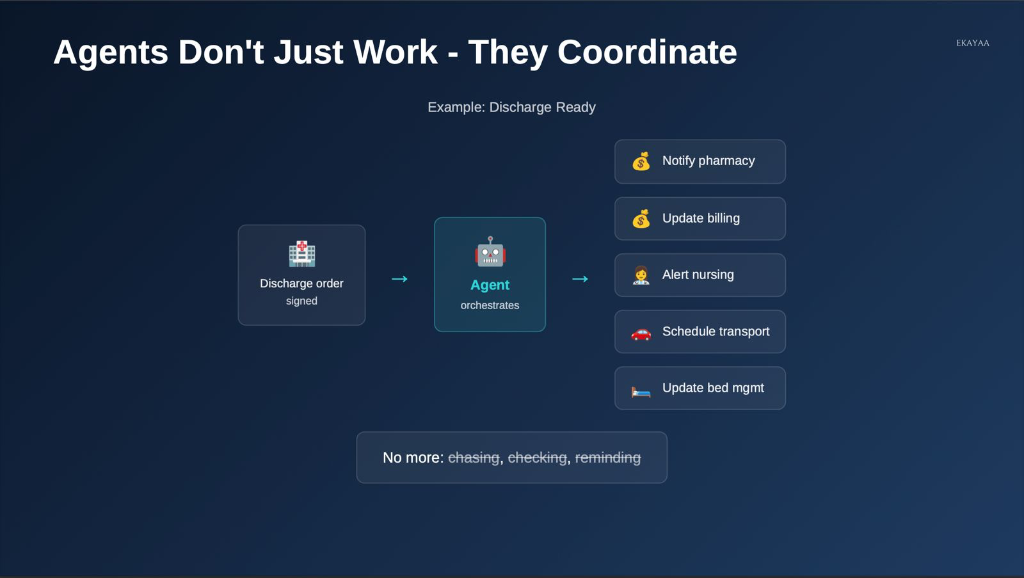

Orchestrating the "Discharge Ready" Flow

In a complex hospital workflow, agents don't just work in isolation; they coordinate entire cross-departmental sequences. For example, once a discharge order is signed, an agent can automatically notify pharmacy, update billing, alert nursing, and schedule transport.

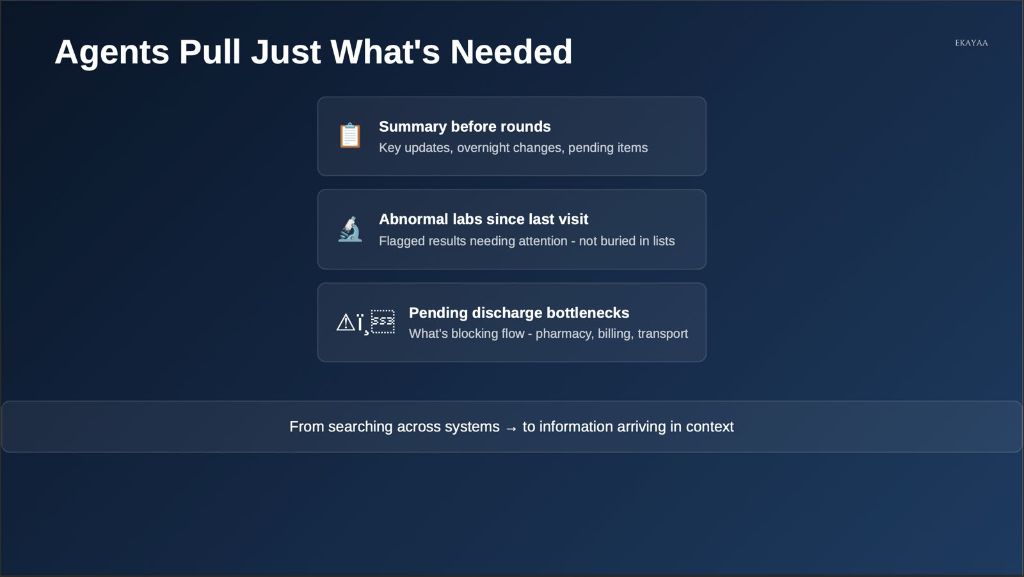

Information in Context

By pulling exactly what is needed—summaries before rounds, abnormal labs, or discharge bottlenecks—agents turn searching across systems into information arriving exactly in context.

Agentic AI: A New Vision for Hospital Operations

One of the most forward-looking themes of the session was the definition of Agentic AI and its role in fundamentally transforming how hospital systems work.

Current Systems vs. The Agentic Shift

Traditional hospital systems (HIS/EMRs) are historically static gateways. They require high manual effort to "input" data and often act as digital filing cabinets that respond only to direct human commands.

In contrast, Agentic AI represents a shift toward:

- Autonomy: Systems that don't just store data but take proactive actions based on clinical goals.

- Real-Time Orchestration: Moving from periodic "data entry" to a continuous flow of assistance that moves with the surgical or clinical team.

- Why it's Different: Unlike previous AI generations that were purely analytical (identifying patterns), Agentic AI is operational—it can navigate workflows, coordinate between departments, and assist in real-time decision-making.

The Three Pillars of Agentic Operations

The vision for the future hospital is built on three core operational principles:

- Intelligent: The system provides more than just data storage; it offers real-time insights and automated orchestration of the patient journey.

- Adaptive: The technology is designed to thrive in the dynamic, high-pressure environment of a hospital. It adjusts to emergencies, resource shifts, and changing clinical priorities in real-time.

- Human-Centric: Most importantly, the technology is built around the humans who use it. It aims to reduce the "operational load" on clinicians, allowing them to focus on the patient rather than the screen.

Smart OT & TeleICU: The High-Tech Clinical Core

Dr. Prabhu shared a deep dive into the high-capital, high-tech environments where digital integration is most critical.

-

Smart OT (Operation Theatre):

- Interconnectivity: Modern OTs feature interconnected systems where real-time data feeds from surgical equipment are automatically captured into the electronic surgical record (ESR).

- IoT & Sensors: The environment is heavily instrumented with IoT sensors and AI analytics to optimize surgical workflows and patient safety.

- Remote Assistance: Digital imaging and tele-medicine allow for real-time remote assistance from specialists during complex procedures.

-

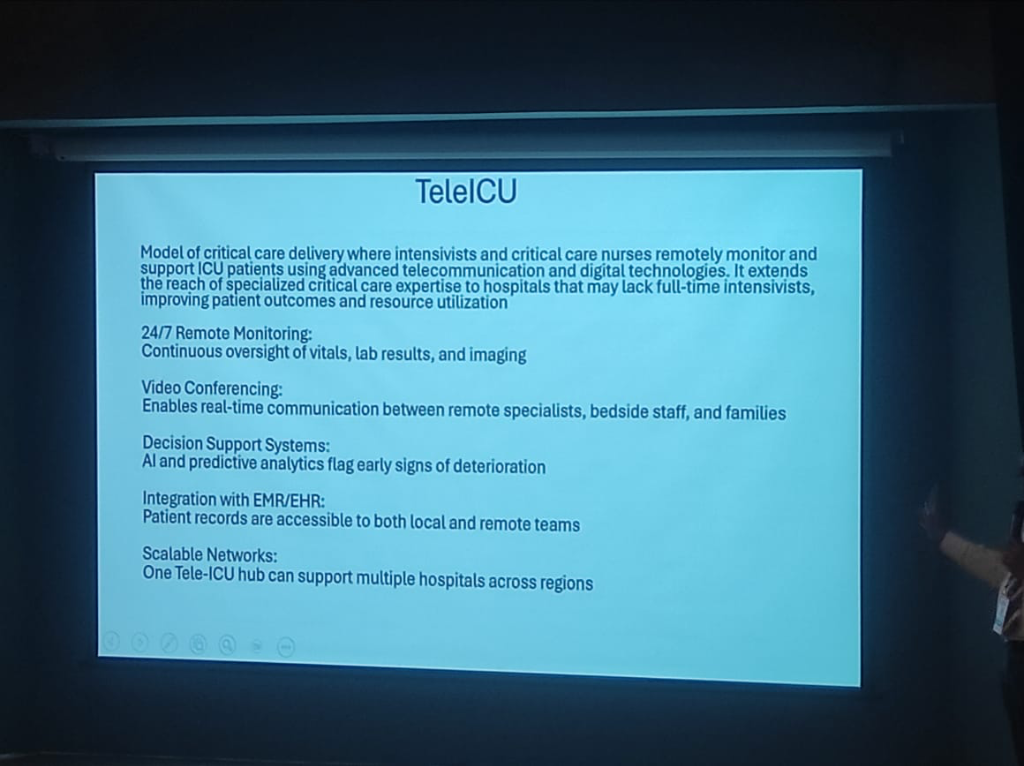

TeleICU: Scalable Critical Care:

- The Hub-and-Spoke Model: A central Tele-ICU hub can support multiple hospitals across different regions, extending specialized critical care expertise to facilities that lack full-time intensivists.

Figure: The architecture of a scalable TeleICU network, featuring remote monitoring and AI decision support.

Figure: The architecture of a scalable TeleICU network, featuring remote monitoring and AI decision support.

- 24/7 Monitoring: Intensivists and nurses remotely monitor vitals, lab results, and imaging data around the clock.

- AI Decision Support: Advanced analytics and predictive AI flag early signs of patient deterioration, allowing for proactive intervention.

- Video Collaboration: Enables real-time communication between remote specialists, bedside staff, and families.

Specialized Systems: LIMS & AI Radiology

The digitization of clinical ecosystems is completed by specialized, high-fidelity systems.

- LIMS (Laboratory Information Management): These systems manage the entire lifecycle of a medical laboratory—from sample tracking and testing to processing and reporting—ensuring end-to-end data integrity.

- AI in Radiology (PACS/RIS): The radiology field is highly mature in its use of AI. Images captured via PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) are now routinely interpreted by AI algorithms to generate high-accuracy preliminary reports, freeing up radiologists for more complex cases.

Data Architecture: Managing Volume, Velocity, and Variety

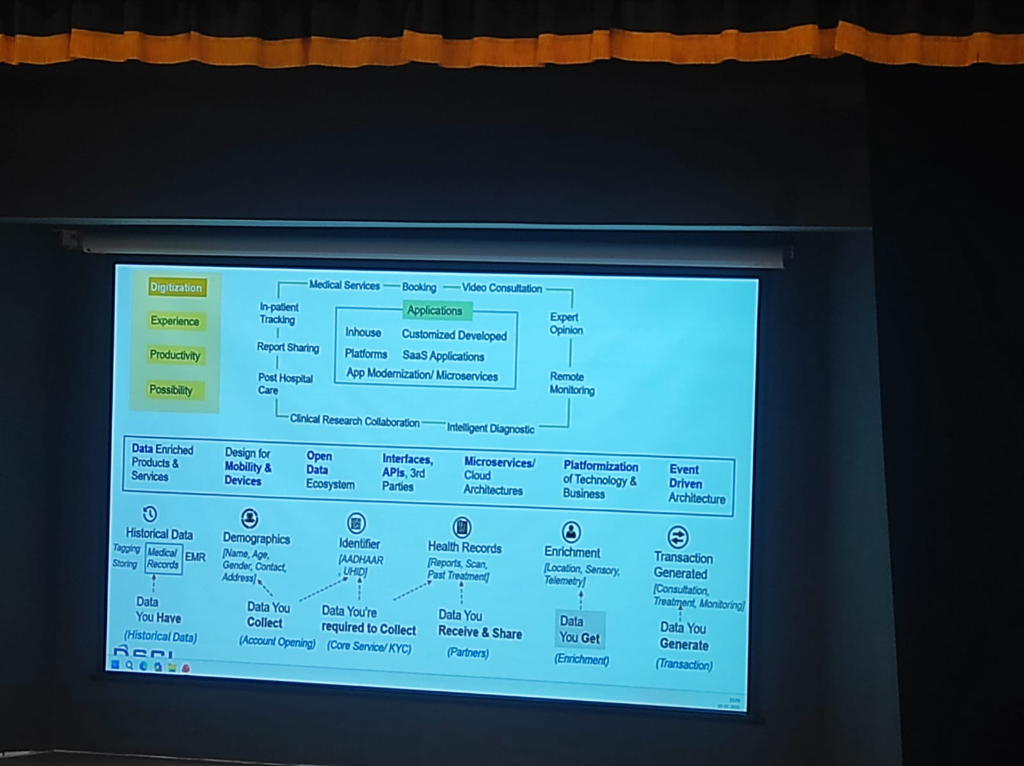

The digital health ecosystem is characterized by an explosion of Heterogeneous Data. As clinical services expand from in-patient tracking to remote monitoring and intelligent diagnostics, the technical architecture must evolve to handle the increasing Volume and Velocity of data flows.

Figure: The 6-step clinical data journey—from historical records to transaction-generated insights.

Figure: The 6-step clinical data journey—from historical records to transaction-generated insights.

Successful digital health platforms manage data through a structured lifecycle, as demonstrated in the national framework:

- Historical Data (What you Have): Digitizing legacy medical records and EMR tagging.

- Demographics (What you Collect): Initial account opening and patient identification.

- Identifier (What you're Required to Collect): Anchoring the patient to national standards (ABHA/UHID).

- Health Records (What you Receive & Share): Interoperable exchange of clinical reports and scans with partners.

- Enrichment (What you Get): Adding sensory, telemetry, and location data to the patient profile.

- Transaction Generated (What you Generate): The final clinical outcome—consultations, treatments, and continuous monitoring.

App Modernization & Microservices

To prevent architecture stagnation, hospitals are shifting toward App Modernization. This involves moving from rigid, monolithic HIS systems to Microservices and SaaS-based cloud architectures. This modularity is essential for scaling Intelligent Diagnostics and facilitating Clinical Research Collaboration across institutions.

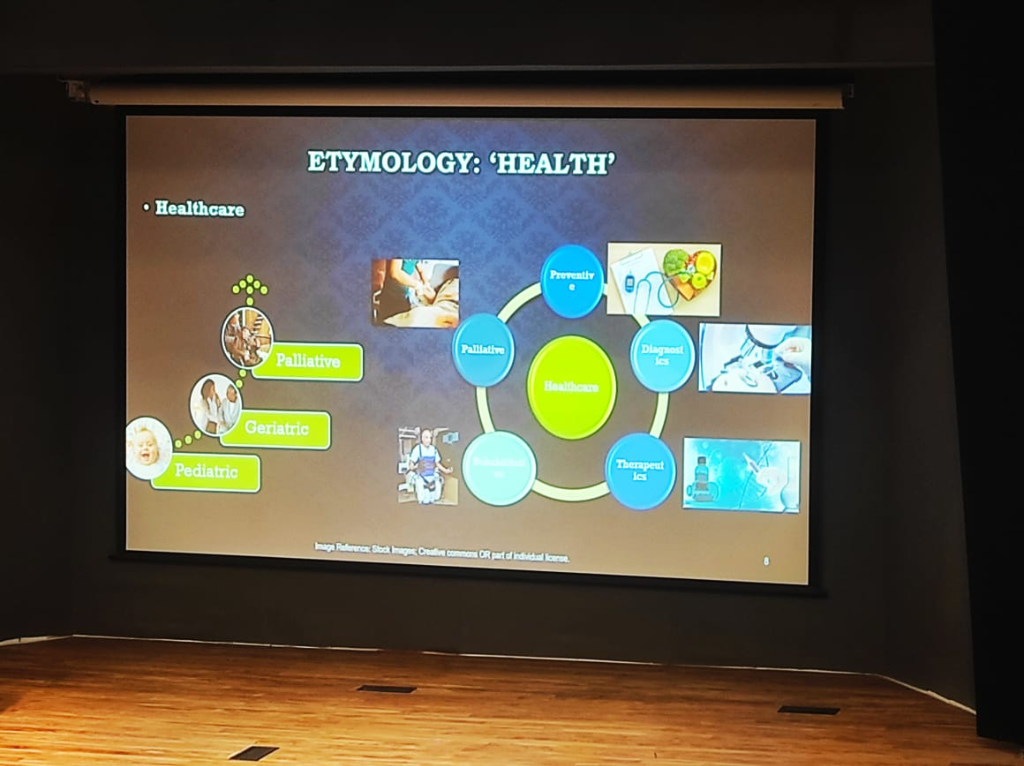

The Spectrum of Healthcare Data

Before diving into infrastructure, it is vital to understand the diversity of data that flows through a digital health ecosystem. Medical data is not just an EMR; it is a complex mosaic of diverse identifiers and sources, influenced heavily by Who is being monitored and How the components integrate.

Figure: The holistic landscape of healthcare—integrating Preventive, Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Palliative care across diverse patient cohorts from Pediatric to Geriatric.

Figure: The holistic landscape of healthcare—integrating Preventive, Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Palliative care across diverse patient cohorts from Pediatric to Geriatric.

The System Dilemma: Cohorts & Complexity

Any digital health strategy must account for two critical variables that define its clinical and technical success:

- Cohort-Specific Significance: The clinical relevance of data is not absolute; it is relative to the patient population. Clinical baselines and urgency thresholds shift dramatically across the life-cycle—from Pediatric to Geriatric and eventually Palliative care. A data point that is merely "noise" in one group may be a "critical signal" in another.

- The Debugging Paradox: In health tech, "debugging" is rarely about fixing a single broken component. Individual parts—a wearable sensor, a cloud API, or an EHR database—often function perfectly in isolation. The real challenge emerges when these Individual Components Come Together. Addressing problems in such a system requires a "systems-thinking" approach to identify failures at the integration points rather than within the components themselves.

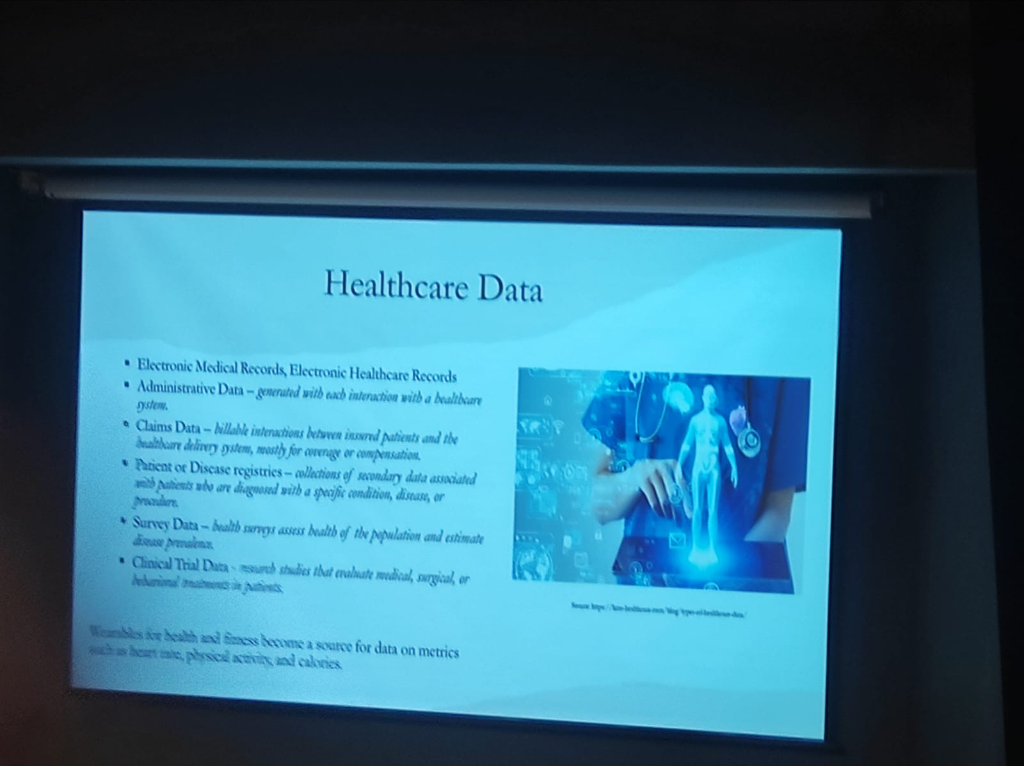

Figure: The diverse landscape of healthcare data—from clinical EMRs and administrative records to billable claims, disease registries, health surveys, and wearable-generated metrics.

Figure: The diverse landscape of healthcare data—from clinical EMRs and administrative records to billable claims, disease registries, health surveys, and wearable-generated metrics.

- Electronic Medical & Health Records (EMR/EHR): The core clinical longitudinal record.

- Administrative Data: Generated with every system interaction (registrations, scheduling, bed management).

- Claims Data: Billable interactions between insured patients and the healthcare delivery system, primarily for coverage and compensation.

- Patient or Disease Registries: Secondary data associated with patients diagnosed with specific conditions (e.g., Oncology or Cardiac registries).

- Survey Data: Health surveys that assess the health of the population and estimate disease prevalence.

- Clinical Trial Data: Research studies that evaluate medical, surgical, or behavioral treatments in patients.

- Wearable & Fitness Data: A growing source of continuous metrics such as heart rate, physical activity, and calories. Consumer ecosystems like Apple Health are now collecting more data than most patients realize, making institutional governance of this stream increasingly critical.

The Continuous Monitoring Revolution: Primary vs. Derived Data

The integration of wearables marks a shift from periodic snapshots to Continuous Scanning. However, a foundational principle must guide this integration: Medical-grade wearables and consumer-grade devices are not the same.

While consumer ecosystems like Apple Health are prolific, they primarily offer Surrogate or Derived Data, which must be distinguished from Primary Clinical Data:

- Primary Data: Direct, raw clinical measurements or waveforms (e.g., a chest ECG patch providing raw electrical activity).

- Derived & Surrogate Data: Algorithmic outputs that proxy clinical states. For instance, HRV, Heart Rate, and Respiratory Rate on consumer smartwatches are often derived via PPG (photoplethysmogram) sensors and proprietary algorithms.

- The Informed Second Opinion: Managed effectively, these provide a valuable "informed second opinion" for pre-clinical tracking and medication titration, but they carry inherent technical risks:

- False Positives & Alarm Fatigue: Consumer-grade ecosystems (Apple, Garmin, Smart Rings, and even consumer Chest Straps) frequently generate false positives. Without clinical-grade filtering, these signals can lead to unnecessary patient anxiety and clinician "alarm fatigue."

- Technical Artifacts: Motion artifacts can significantly distort readings from consumer-grade trackers during daily activity.

- Biochemical Dependencies: Precision varies by technology. For example, Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) use enzymatic reactions (glucose oxidase) that are sensitive to underlying oxygen level fluctuations or respiratory disorders.

- Algorithmic Opacity: Unlike clinical-grade equipment, consumer devices often lack transparent algorithmic validation for their derived parameters.

- Snapshot vs. Continuous Monitoring: A critical void exists in measurement duration and continuity. An Apple Watch ECG, for instance, is an on-demand 30-second snapshot—functionally different from hospital-grade continuous telemetry.

- The CGM "Closed-Loop" Gap: While CGM patches provide more frequent data, they are limited by wearable duration (sensor drift after 10-14 days) and, critically, a lack of Closed-Loop integration. In consumer-grade tech, the data is often "monitoring-only," lacking the integrated therapeutic response required for clinical management.

Wearable Intelligence: Extracting Signal from Noise

The true "intelligence" of a wearable does not reside in the hardware module but in the Algorithm. This is especially critical because Raw Data is Junk from a clinical perspective, particularly when the user is active.

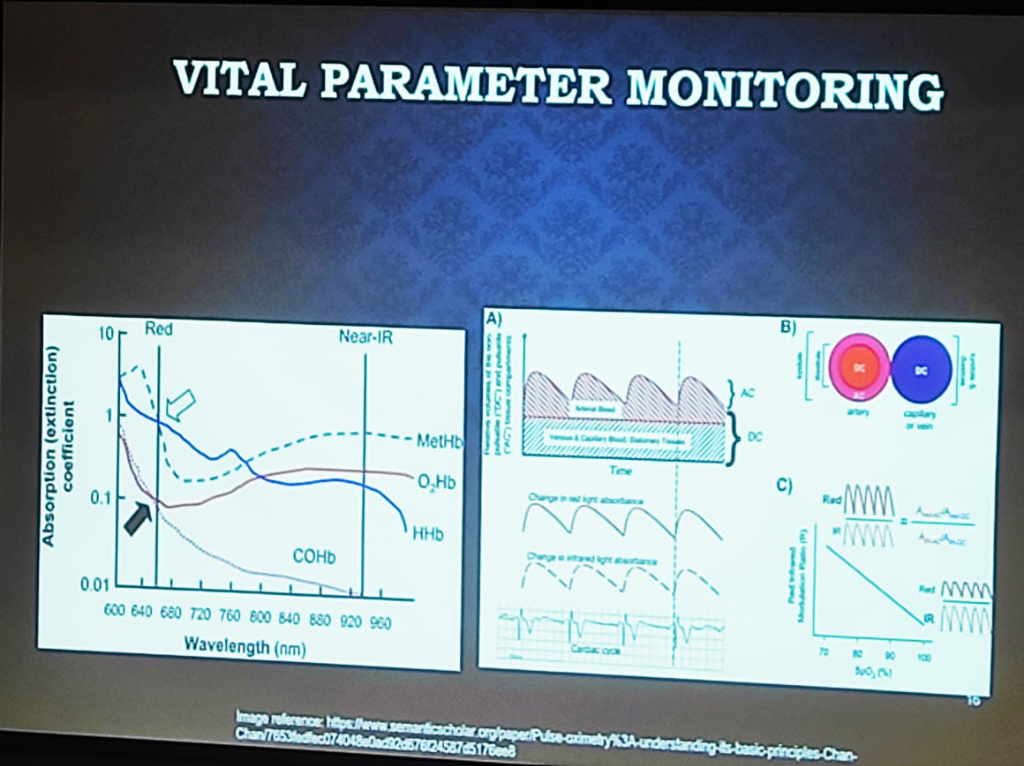

Figure: The physics of Vital Parameter Monitoring—showing the absorption (extinction) coefficients of hemoglobin states and the separation of pulsatile (AC) and stationary (DC) signal components.

Figure: The physics of Vital Parameter Monitoring—showing the absorption (extinction) coefficients of hemoglobin states and the separation of pulsatile (AC) and stationary (DC) signal components.

- The Pulse Oximetry (PPG) Spectrum:

- Medical-Grade: Uses a combination of Red and NIR (Near-Infrared) wavelengths. It relies on the ratio of the pulsatile (AC) part to the stationary (DC) part of the signal across both wavelengths to calculate oxygen saturation accurately.

- Consumer-Grade: Often uses Green Wavelengths (providing maximum reflectance) for heart rate tracking. While these devices handle Single-Point (Snapshot) measurements reasonably well, maintaining clinical significance and signal integrity Over Time (Longitudinal) is a significantly greater engineering hurdle. Baseline drift, changing sensor-to-skin contact, and environmental fluctuations make consistent long-term monitoring with consumer hardware a complex algorithmic challenge.

- Mechanical Interference (The "Tight Wear" Problem): Signal integrity is sensitive to physical application. A common clinical error in consumer wearables is excessive wearing pressure. Wearing a smartwatch or ring too tightly can compress the underlying capillaries and venous structure, distorting the pulsatile (AC) components and altering the stationary (DC) baseline. This mechanical interference leads to incorrect parameter extraction, as the algorithms cannot distinguish between physiological pulse and pressure-induced artifacts.

- Environmental & Chemical Dependencies: precision varies by the underlying technology and ambient conditions:

- Trend over Truth (Absolute Value Inaccuracy): A critical clinical caveat for Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) is the inherent inaccuracy of Absolute Values. Most consumer and intermediate-grade CGMs are not designed for the same level of spot-check precision as clinical finger-prick glucometers. However, in clinical practice, the Trend and Range (Time-in-Range) provided by the CGM is more than enough for effective monitoring and behavioral intervention. The clinical utility lies in revealing longitudinal patterns and glycemic variability over time, rather than absolute precision at any single moment.

- Biochemical & Non-Invasive CGMs: Traditional monitors use enzymatic reactions (glucose oxidase) sensitive to oxygen levels. However, next-generation Non-Invasive Glucose Monitoring (e.g., smart rings or PPG-based patches) faces two massive engineering hurdles:

- The Water Interference Problem: Glucose has specific absorption peaks (e.g., 850nm, 950nm, 1150nm), but these often overlap with water content peaks. Since the human body is primarily water, extracting the "glucose signal" from the "water noise" is a significant technical challenge.

- The Calibration Void: There is no universal calibration curve for non-invasive sensing. Individual physiological variability (Skin Type, Body Type, Hydration) means that "Person A" and "Person B" will have completely different absorption characteristic curves for the same glucose level. Accuracy requires combining raw PPG data with patient-specific parameters via an AI Intelligence Layer to create personalized calibration models.

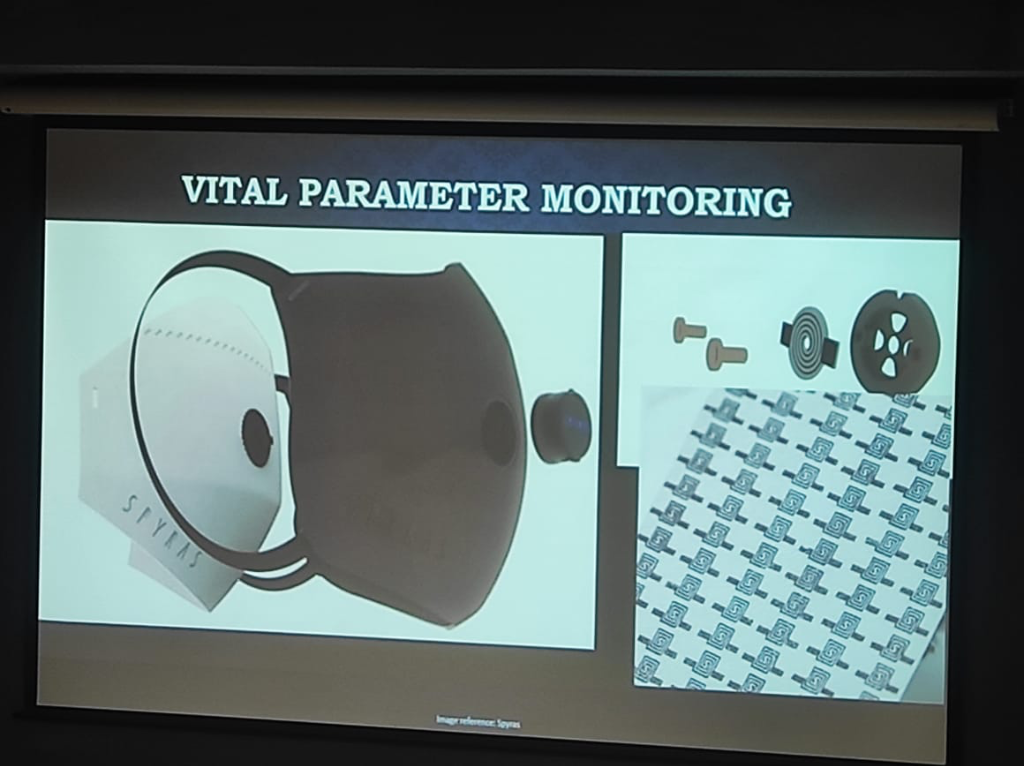

- Humidity vs. Mechanical Strain: Respiratory monitoring reveals a critical technical divide. Chest Straps measure lung expansion via mechanical strain, while newer mask-integrated sensors (as shown below) may rely on Humidity Levels and airflow. Environmental factors like ambient humidity can create significant discrepancies between these modalities when measuring lung capacity, requiring complex compensation algorithms to ensure clinical accuracy.

Figure: Advanced Respiratory Monitoring—demonstrating the integration of sensors into masks to capture vital parameters via airflow and humidity, moving beyond simple mechanical chest straps.

Figure: Advanced Respiratory Monitoring—demonstrating the integration of sensors into masks to capture vital parameters via airflow and humidity, moving beyond simple mechanical chest straps.

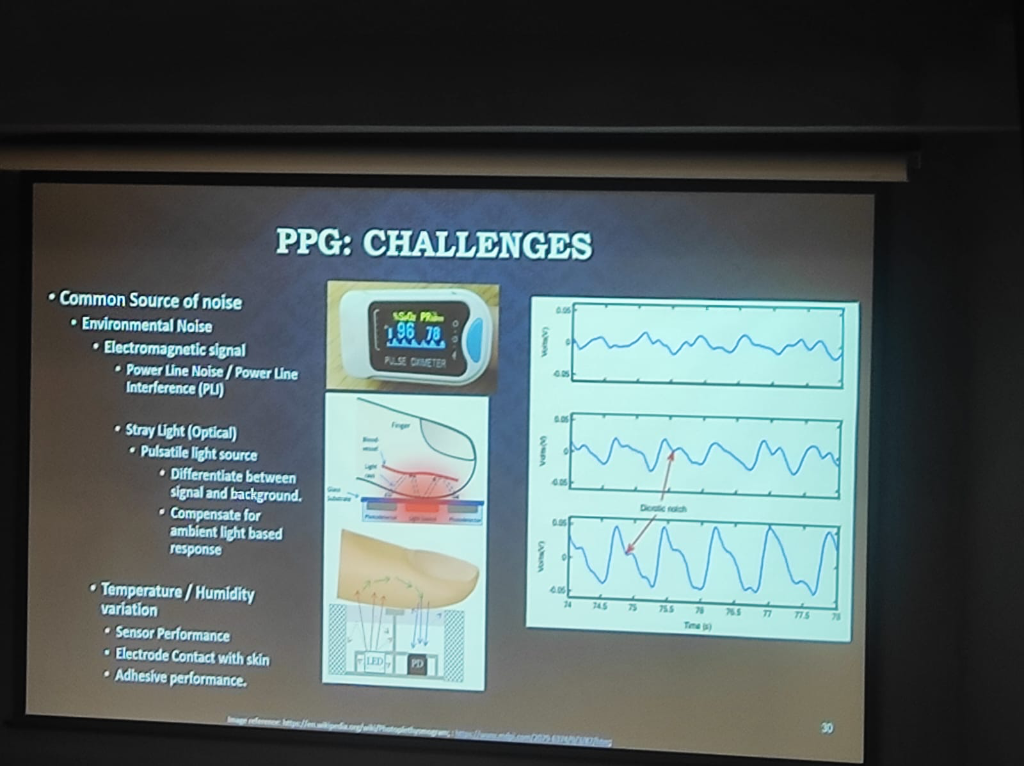

- The Multi-Factor Noise Landscape: Beyond motion, PPG signal integrity is threatened by a spectrum of environmental and mechanical noise sources that engineering teams must address through Device Geometry and signal processing:

- Environmental Optical Noise: Sensors must differentiate between the pulsatile clinical signal and ambient stray light. This requires complex compensation for background lighting to prevent signal saturation.

- Electromagnetic Interference (EMI): Power line noise and interference (PLI) can introduce electrical artifacts that mimic physiological rhythms.

- Temperature & Sensor Performance: Thermal variations can affect sensor sensitivity, electrode-to-skin contact, and the performance of medical adhesives, creating a shifting baseline for data extraction.

Figure: The spectrum of PPG Challenges—detailing environmental noise (EMI, Stray Light) and the impact of temperature/humidity on sensor and electrode performance.

Figure: The spectrum of PPG Challenges—detailing environmental noise (EMI, Stray Light) and the impact of temperature/humidity on sensor and electrode performance.

Engineering Actionable Data: Beyond the API

Creating an actionable EHR from wearable data requires solving five critical engineering and clinical challenges:

- The Semantic Gap (Algorithm Variance): Identical units (e.g., milliseconds) do not guarantee identical meaning. For instance, Heart Rate Variability (HRV) can be calculated via different formulas—Standard Deviation of NN intervals (SDNN) vs. Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD). Different devices (Apple, Garmin, Fitbit) generate proprietary "Sleep Scores" or "Stress Scores" that are not semantically comparable. Bridging this gap requires mapping diverse algorithmic outputs to a unified clinical standard.

- The Temporal Gap (Continuance vs. Episodic): Modern EHRs are fundamentally built for Episodic Data—capturing distinct clinical events (visits, labs, surgeries). In contrast, wearables generate a Continuous High-Frequency Stream. Injecting raw continuous data into an episodic HIS causes "storage bloat" and clinician data-overload. System architects must implement "intermediate refinement" layers that convert continuous streams into meaningful episodic summaries or "parameter reports" (as seen in CGM reports) before EHR injection.

- Activity-Aware Normalization: Raw data is meaningless without context. Normalization must be "activity-aware" to create valid Optimal Baselines. Heart rate during sleep vs. heart rate during a marathon are two different data points; without normalization, they cannot be used to detect clinical anomalies.

- Contact Verification: Physiological significance relies on signal quality. Modern clinical governance must include algorithms to verify appropriate body contact, ensuring the device hasn't slipped or lost its sensor-to-skin integrity.

- Clinical Workflow Integration: The final metric of success for wearable data is not technical accuracy, but its impact on the clinical workflow. Global precedents, such as Mayo Clinic's integration of Apple Watch data and Western institutional CGM-based studies, demonstrate that integration must prioritize Burden Reduction for clinicians:

- Event-Based vs. Continuous Flow: Systems should move away from dumping continuous raw datasets. Instead, integration should be Event-Based—where specific algorithmic triggers (e.g., a detection of sustained tachycardia or oxygen desaturation) inject data into the EHR only when clinical attention is warranted.

- Longitudinal Trend Summaries: Clinicians need the ability to view deterioration over time. Rather than relying on proprietary manufacturer scores (which are often "black boxes"), institutions should define their own Clinical Indices for trend-based analysis.

- The Actionable Loop (Medication Continuity): Successful models involve Weekly Summaries where data trends are reviewed to provide active clinical recommendations. This includes adjustments for Medication Continuity, ensuring that wearable data isn't just monitored but used to close the therapeutic loop.

- Data Parsimony & Clinical Intent: We must question the volume of data collected based on clinical objectives. For instance, CGM monitoring for a patient not at risk of hypoglycemia may only require a 14-day trend to capture intermediate glycemic variability—after which the utility of continuous data plateau. Conversely, Cardiac monitoring requires long-term longitudinality and high-resolution indices. In clinical practice, Indices are more important than raw data volume.

- Human-in-the-Loop Escalation: Actionable data must be embedded within an escalation logic. This includes sharing data to ICU-style workstations with clear escalation paths and maintaining a "Human-in-the-Loop" for final therapeutic decisions.

- The Practical Delivery Gap (Email/WhatsApp vs. EHR): A major hurdle in the current landscape is the delivery modality. Most CGM data reports are currently shared via Email or WhatsApp rather than being natively integrated into a professional EHR. This creates a fragmentation gap where vital wearable insights exist as loose attachments or messages rather than being part of a structured, longitudinal clinical history. True integration requires moving these reports from consumer apps into the core clinical information system.

- Proximity vs. Significance: A foundational clinical principle is that physical proximity does not correlate to physiological significance. A recent example is the Zomato CEO wearing a CGM (Continuous Glucose Monitor); while the device was physically attached and generating data, its physiological significance is limited when used by a healthy individual without clinical indication. Data without clinical intent is merely noise, not medicine.

The Data Lifecycle: A Governance Framework

Managing this diverse data requires a structured lifecycle approach. As hospitals transition to "Privacy-First" architectures, the process of how data is collected, used, and shared becomes more important than the simple act of storage.

Figure: The 5-stage Data Lifecycle—Capture, Process, Use, Store, and Dispose—providing the foundational timeline for clinical data governance.

Figure: The 5-stage Data Lifecycle—Capture, Process, Use, Store, and Dispose—providing the foundational timeline for clinical data governance.

- Capture: Securely ingest data into health information systems from clinical, administrative, or wearable sources.

- Process: A series of automated and manual actions taken to create and offer clinical products and health services.

- Use: The critical phase of Access, Sharing, and Analysis. This is the most important process for most modern systems, where governance must be strictly enforced.

- Store: Maintaining and archiving data in encrypted, high-availability environments.

- Dispose: The often-neglected final step—ensuring secure destruction per retention schedules to limit long-term liability.

At every stage of this lifecycle, hospitals must adopt the principle of Data Minimization:

- Lower Costs: Collecting only what is necessary reduces the massive storage and processing overhead on clinical infrastructure.

- Reduced Risk: Minimizing the data footprint directly lowers the surface area for potential breaches and DPDP liability.

- Privacy by Default: Moving from "collect everything" to "collect what is required" is the cornerstone of a modern, compliant health system.

Infrastructure Essentials: The "Hardware Blind Spot"

A critical gap in digital health transformation is the clinician's awareness of the underlying physical infrastructure. Successful implementation requires understanding the Bill of Materials (BOM) and the foundational requirements for operational stability.

The maturity of a hospital's digital infrastructure is often determined by its location. The City Classification (Tier 1 vs. Tier 2/3) dictates the "Class of Hardware" available and the feasibility of cloud-native deployments:

- Tier 1 Cities: High bandwidth availability and reliable power make Cloud-Native architectures and advanced hardware deployments more feasible.

- Tier 2/3 Cities: Internet instability often mandates a Heavily On-Premise or hybrid approach, with specialized ruggedized hardware to handle environmental stressors.

For a hospital to function digitally, the infrastructure must be treated with the same rigor as surgical equipment:

- Networking as a Priority: Enterprise-grade networking is the most underestimated cost. High-performance managed switches and robust structured cabling (Cat6/Fiber) are essential to prevent the "system is slow" bottleneck.

- The Power Factor: Redundant power supplies and industrial-grade UPS systems are non-negotiable for 24/7 clinical continuity.

- Terminal Devices: A mix of specialized medical-grade tablets, bedside terminals, and high-resolution diagnostic monitors.

Mission-Critical Design: "Running with Hands Tied"

In many clinical settings, direct internet access is prohibited for security reasons. Designing for these "air-gapped" or restricted environments requires a shift in engineering philosophy toward high availability and resilience.

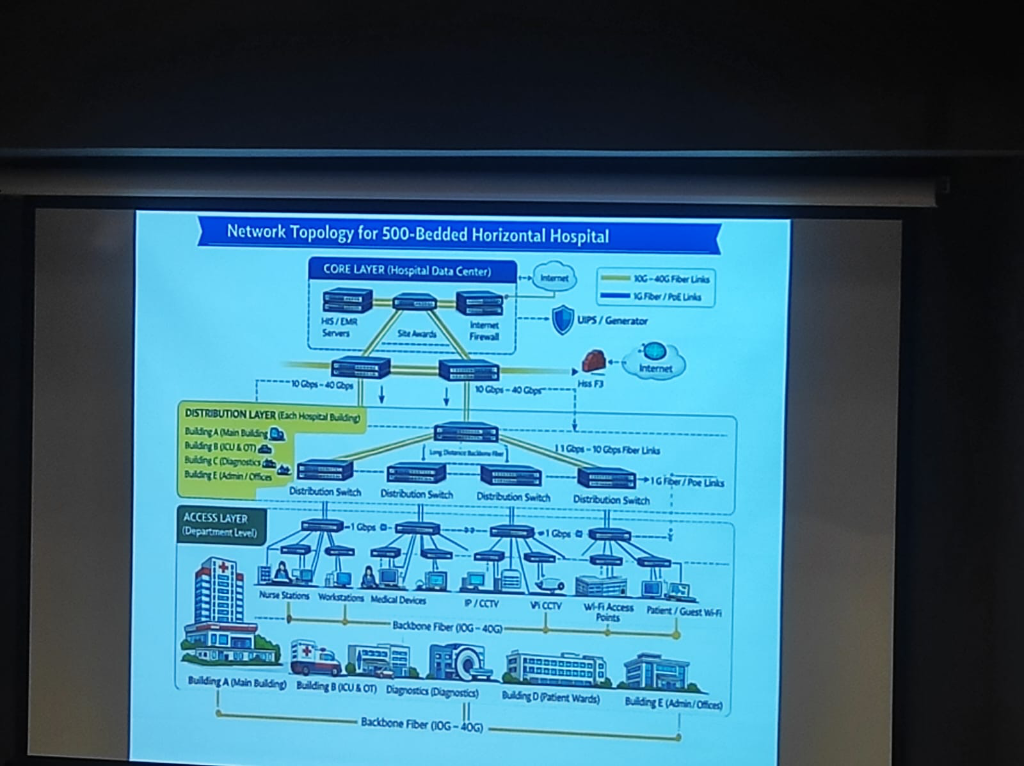

Hospital Network Topology

For a 500-bed hospital, the network must be tiered to ensure that a failure in one ward doesn't paralyze the entire institution:

Figure: A formal 3-layer topology (Core, Distribution, Access) designed for zero-downtime clinical operations.

Figure: A formal 3-layer topology (Core, Distribution, Access) designed for zero-downtime clinical operations.

- Advanced Availability Architecture: Hospitals must eliminate single points of failure through a robust technology stack:

- High Availability (HA) & Clustering: Grouping servers into clusters to ensure that if one node fails, another takes over instantly without service interruption.

- Data Replication: Real-time mirroring of clinical databases across multiple storage engines to prevent data loss.

- Failover & Disaster Recovery (DR): Automated failover mechanisms to a secondary Disaster Recovery site (on-prem or cloud backup) ensuring continuity during catastrophic failures.

- Zero-Downtime Resilience: Hospitals cannot afford a "wait period." Systems must be designed for Triple Redundancy (Local, On-Prem Backup, and DR site) to ensure clinical continuity 24/7.

- PAC Systems & High Throughput: Medical imaging (PACS) generates massive data volumes. This requires High-Throughput Storage and dedicated high-speed VLANs to ensure radiologists and surgeons can access 3D scans instantly without network lag.

- Scalability for Expansion: Infrastructure must be modular, allowing for "plug-and-play" expansion of departments without overhauling the core network backbone.

Threat Vectors in Healthcare

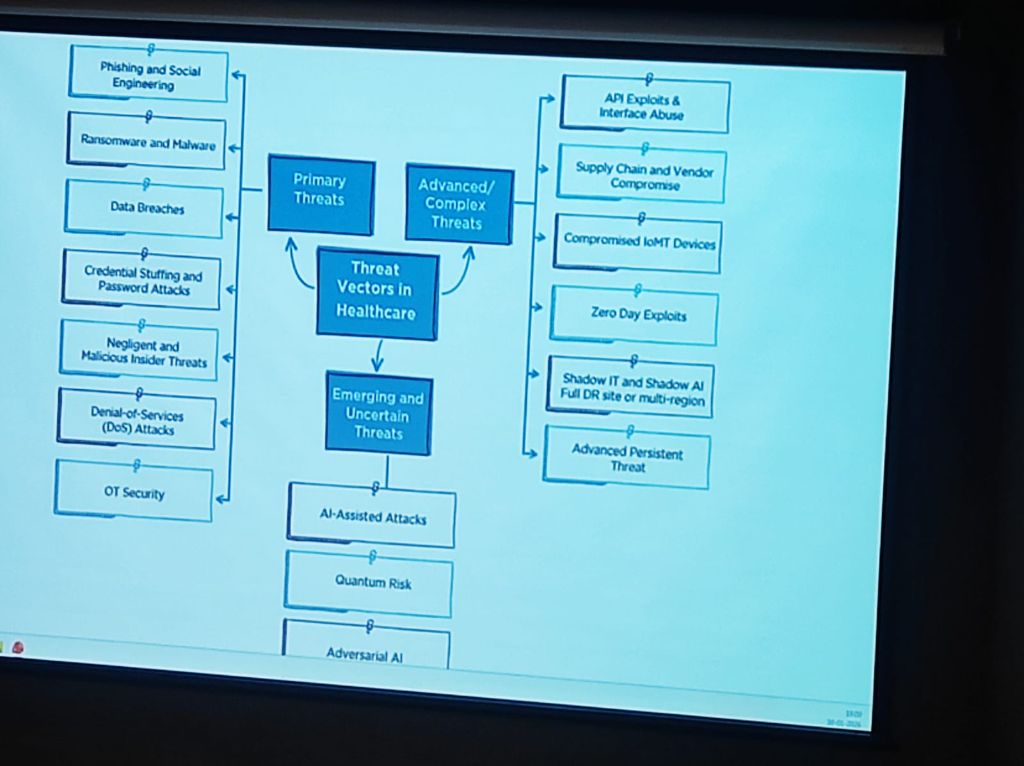

The risk landscape in healthcare has evolved into a multi-layered challenge. As per DSCI’s analysis, these threats can be categorized into three distinct tiers:

- Primary Threats: The foundational risks including Phishing and Social Engineering, Ransomware and Malware, Data Breaches, Credential Stuffing, and Insider Threats (both negligent and malicious).

- Advanced & Complex Threats: Highly targeted attacks such as API Exploits, Supply Chain/Vendor Compromise, Compromised IoMT (Internet of Medical Things), Zero Day Exploits, and Shadow IT/AI.

- Emerging & Uncertain Threats: The next generation of risks featuring AI-Assisted Attacks, Quantum Risk, and Adversarial AI.

Figure: The evolving landscape of threat vectors in healthcare—from primary breaches to emerging quantum and AI risks.

Figure: The evolving landscape of threat vectors in healthcare—from primary breaches to emerging quantum and AI risks.

Implementing Technical Measures: A 4-Pillar Roadmap

To counter these evolving threats, institutions must move from theoretical security to a rigorous technical implementation roadmap:

- Restrict Access & Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Access must be strictly limited to authorized users only. Implementing Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) across all clinical and administrative applications is non-negotiable for securing the entry points of the HIS.

- Periodical Risk Assessments: Security is dynamic. Hospitals must conduct regular risk assessments to identify technical vulnerabilities, internal loopholes, and the security posture of third-party vendors, service providers, and associates.

- Data Encryption at Scale: Comprehensive Data Encryption must be enforced throughout the information lifecycle—securing data both In Transit (across networks) and At Rest (on storage servers).

- Anonymization & Aggregation: To further mitigate re-identification risks, hospitals should utilize aggregated datasets which significantly decrease the chances of a specific individual being pinpointed from a larger data set.

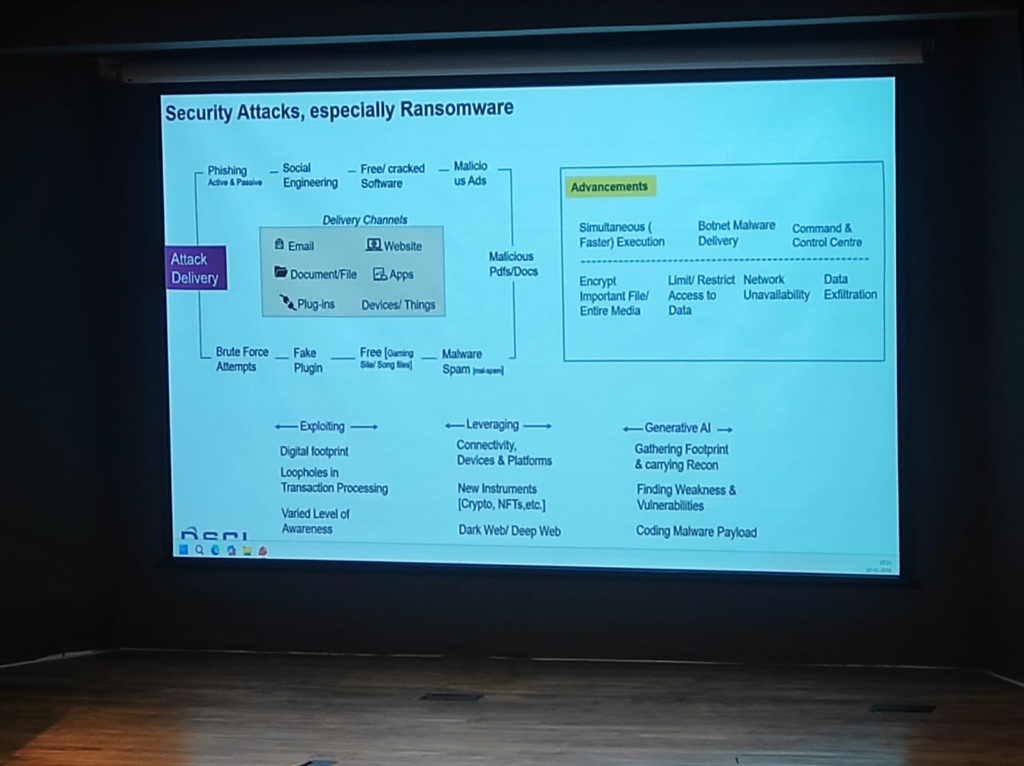

Ransomware attacks in healthcare are no longer just about encryption; they have become highly advanced technical operations:

- Simultaneous Execution: Modern ransomware executes faster across entire networks, encrypting important files and media simultaneously to prevent manual intervention.

- Botnet & Malware Delivery: Attackers use sophisticated Botnet delivery channels and Command & Control (C2) centers to automate the exfiltration of sensitive patient records.

- The Gen-AI Lowering the Bar: Generative AI has made exploitation easier than ever. It enables attackers to gather footprints, find vulnerabilities, and code malicious payloads with minimal specialized effort.

- A Shared Ecosystem Mandate: This heightened risk requires a unified awareness across the entire ecosystem—Health Providers, Medtech companies, Government agencies, and Insurance providers must all adopt a "Response & Recovery" first mindset.

Figure: The technical advancements in ransomware delivery and the role of Generative AI in lowering the barrier for clinical exploitation.

Figure: The technical advancements in ransomware delivery and the role of Generative AI in lowering the barrier for clinical exploitation.

A pervasive but dangerous reality in Indian healthcare is the use of consumer messaging apps like WhatsApp for clinical data exchange:

- Zero Audit Trails: Unlike institutional EMRs, consumer apps provide no standardized logs of who accessed what data and when, making forensic analysis impossible after a breach.

- DPDP Non-Compliance: Sharing personally identifiable health information (PII/PHI) on unmanaged consumer platforms is a direct violation of the DPDP Act. The institution—not the app provider—remains liable for the data leakage.

- The "Shadow Data" Problem: Once a medical report is shared on WhatsApp, it exists in an unmanaged, unencrypted-at-rest state on personal devices, bypassing all institutional security perimeters.

The processing of Insurance Claims and TPA (Third-Party Administrator) interactions remains one of the most neglected areas of data security in Indian healthcare:

- Neglected Security Protocols: While internal clinical systems are increasingly secured, the data sent to insurers often lacks rigorous security SOPs.

- Unsafe Sharing Habits: Sensitive patient claims data is frequently shared through unmanaged, unsecured channels, creating massive exposure risks for both the patient and the hospital.

- The Compliance Gap: Under DPDP, the hospital remains the primary data fiduciary—liable for how the patient's data is handled even when it leaves the premises for insurance processing.

Hospitals often generate and share massive datasets related to Health Surveys and Clinical Trials. These "large-set" exchanges present unique architectural and security challenges:

- Pseudonymization vs. Anonymization: A critical distinction for large-scale data governance:

- Pseudonymization: A technical measure where personal identifiers are replaced by codes. This process is reversible (with a key) and the data is still classified as Personal Data under DPDP.

- Anonymization: A process that irreversibly removes personal identifiers, ensuring the data cannot be traced back to an individual. Anonymized data is generally exempt from certain DPDP processing restrictions.

- The Aggregation Fail: Large datasets are frequently shared in their raw, granular form without proper aggregation, making it easier to re-identify individuals from supposedly "anonymous" lists.

- Mandatory Protocols: For research and survey data to be safe, it must undergo rigorous pseudonymization or anonymization protocols. This ensures that the data is useful for population health analytics without compromising the privacy of the participants.

While the DPDP Act provides certain exemptions for Research, Archiving, and Statistical purposes, these activities must still adhere to rigorous quality standards:

- Lawful Manner: All processing, even for research, must be conducted through legal and ethical frameworks.

- Data Minimization (Necessity): Processing must be limited only to the personal data which is strictly necessary for achieving the research goal.

- Completeness & Accuracy: Researchers are responsible for ensuring the consistency and accuracy of the patient data they handle.

- Reasonable Security Safeguards: Even exempt research data must be protected with modern security measures to prevent leakages.

- Accountability: Every person or institution handling research data remains accountable for the effective observance of these privacy standards.

- Secure Research Sandboxes: Research data should move through managed environments, ensuring that "Person A" cannot be identified through a combination of diverse survey and trial identifiers.

The technical ecosystem of a modern hospital involves dozens of third-party Medtech and software vendors. These represent a major "blind spot" in security governance:

- Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: As seen in global attacks, hackers often target smaller vendors to gain a foothold in larger hospital networks.

- Unmanaged Vendor Access: Allowing vendors "always-on" or unmonitored remote access to clinical systems is a high-risk practice.

- Mandatory Risk Assessments: Institutions must mandate periodic Third-Party Risk Assessments (TPRA) and enforce Least-Privilege Access for all Medtech partners. Managed connectivity (via secure VPCs or ZTNA) is non-negotiable for vendor integrations.

- Contractual Liability: Security is not just technical; it's legal. Vendor contracts must explicitly define breach liability and security standards alignment.

The convergence of rising Quantum complexities, high-velocity data exchanges, and deep cloud dependencies mandates a shift in how hospital architectures are managed:

- Managed Security Architecture: Security is no longer a perimeter firewall; it is a feature of the data flow itself. Architecture must be managed dynamically to counter API exploits, zero-day vulnerabilities, and adversarial AI.

- The Observability Requirement: Hospitals must allocate dedicated budgets for Monitoring and Observability systems. These platforms provide real-time visibility into the "health" of the data ecosystem, detecting anomalies, unauthorized access, and system latencies before they impact patient care.

- Data Flow Integrity: As hospitals become nodes in a national data exchange, observability ensures that every "Scan and Share" or FHIR transaction is secure, audited, and performing at clinical-grade speeds.

As hospitals look toward the future, the role of Artificial Intelligence must be viewed as part of a global paradigm shift. AI is no longer a localized experiment; it is the core engine transforming Autonomous Systems, Manufacturing, Financial Services, E-commerce, Edtech, Space Exploration, Agriculture (Agri), and Cyber Security. Digital Health is the next frontier in this multi-sector revolution, requiring a unique lens for regulatory and security governance:

- Non-FDA Approved LLMs: It is a critical clinical reality that Large Language Models (LLMs) are currently not FDA approved (nor equivalently certified by CDSCO in India) for diagnostic or direct clinical decision-making. They serve as assistive tools, but the clinical liability remains human.

- Diagnostic Accuracy (The Doctor + AI Model): AI is essential for maximizing Diagnostic Accuracy, particularly in screening programs. For instance, Prof. Kshitij Jadhav highlighted a case study on AI-integrated Mammography for breast cancer screening. In India, where there is a high incidence of young breast cancer but no national screening program, a deep learning model was trained to highlight only suspicious lesions and calcifications. By assigning a 1-10 risk score, the AI helps clinicians differentiate between physiological speckles and serious pathologies, significantly improving the "hit rate" compared to systems without AI support.

- Synergy over Replacement: The optimal model remains "Doctor plus AI". The human clinician provides context and nuance, while AI provides the high-velocity pattern recognition required for early detection. The goal is a collaborative synergy where AI acts as a decision-support assistant rather than an autonomous diagnostic "magic wand."

Case Study: AI-Enhanced Triaging Workflow

To visualize why AI is critical for diagnostic accuracy, consider the transformation of the mammography screening workflow (Source: AIDE Lab / KCDH):

graph TD

A[Patient Screening Mammogram] --> B{AI Risk Scoring}

B -- "Low Risk" --> C[Streamlined Review]

B -- "High Risk" --> D[Priority Double Reading]

C --> E[Radiologist Validation]

D --> F[Radiologist 1]

D --> G[Radiologist 2]

F --> H[Consensus]

G --> H

H -- Yes --> I[Final Diagnosis]

H -- No --> J[Senior Radiologist Arbitration]

J --> I

E --> I

style B fill:#e1f5fe,stroke:#01579b,stroke-width:2px

style D fill:#ffebee,stroke:#b71c1c,stroke-width:2px- Standard Workflow (Before AI): Every scan follows a linear path—Radiologist 1 review, followed by Radiologist 2, with the third radiologist acting as an arbitrator only upon disagreement. This is resource-intensive and prone to "screening fatigue."

- AI-Augmented Workflow: The AI system acts as a high-precision triage engine. Scans are assigned a Risk Score (1-10) based on suspicious lesions and calcifications.

- Low-Risk Triaging: Scans with low scores (e.g., 1-5) follow a streamlined validation process.

- High-Risk Prioritization: Scans with high scores (e.g., 6-10) are immediately prioritized for double-reading by specialized radiologists.

- Optimized Recall: By adjusting thresholds, institutions can minimize false positives while ensuring every potential "hit" is captured, maximizing diagnostic accuracy while reducing clinician burden.

| Indicator | Standard Workflow | AI-Augmented Workflow | Impact / Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading Workload | 100% | 66.5% | -33.5% Reduction |

| Cancer Detection Rate | Baseline | Increased | Improved Screening Yield |

| False-Positive Rate | Baseline | Decreased | Reduced Patient Anxiety |

| Turnaround Time | Sequential | Prioritized | Faster High-Risk Results |

Technical Deep Dive: The 4B vs. 1T Parameter Paradox

A critical insight shared during the sessions (Source: Prof. Kshitij Jadhav) centers on the efficiency of AI models in clinical settings.

- The Benchmarking Challenge: Modern LLMs with 1 trillion parameters (often based on massive open-source datasets) reach approximately 90% accuracy on medical benchmarks. However, these models are computationally expensive and difficult to deploy in low-resource clinical environments.

- Ontology-Augmented LLMs: By utilizing Medical Knowledge Graphs and Ontologies (like SNOMED CT) as structured context for LLMs, researchers have achieved a breakthrough in model efficiency.

- Superior Performance at Scale: A specialized 4 billion parameter model, when grounded in a medical knowledge hierarchy, achieves 88-90% accuracy—effectively matching the performance of models hundreds of times its size.

- Low-Resource Deployment: This "Knowledge-First" architecture is essential for India's healthcare landscape, enabling high-precision AI to run on affordable hardware in rural hospitals and clinics where massive GPU clusters are unavailable.

Case Study: Predictive Survival & Triage (Poisoning Control)

Beyond screening, AI is a critical tool for scarce resource allocation. Prof. Kshitij Jadhav discussed a second high-impact use case: Predicting Survival in Rat Poison Ingestion.

graph LR

A[Rat Poison Ingestion] --> B[Integrated Clinical Parameters]

B --> C{AI Prediction Model}

C -- "High Survival Probability" --> D[Supportive Care & Monitoring]

C -- "Critical/Low Survival" --> E[Intensified Triage]

E --> F[Acute Hemodialysis]

E --> G[Liver Exchange Waitlist]

subgraph "Accuracy: 80%"

C

end- The Clinical Challenge: Patients who attempt suicide using rat poison often require intensive supportive therapy, dialysis, or a Liver Exchange.

- Resource Scarcity: India faces a severe shortage of liver donors, making it difficult to decide which patients should be prioritized for transplant vs. supportive therapy.

- The AI Solution: A predictive model was developed to triage these patients. By analyzing clinical parameters, the system achieved 80% accuracy in predicting survival outcomes. This allows clinicians to triage patients effectively, ensuring that high-resource interventions (like liver exchange) are directed where they have the highest probability of life-saving impact.

Case Study: Pan-Cancer Multimodal AI (Histogen)

The frontier of clinical AI lies in Multimodal integration—combining disparate data types for a single patient to enhance Predictive Survival analysis. Prof. Kshitij Jadhav presented the research on Pan-cancer Integrative Histology-Genomic Analysis (Source: Richard J. Chen et al. / AIDE Lab):

graph TD

subgraph "Modality 1: Histopathology"

H["High-Resolution Tissue Images<br/>(WSI)"] --> FE1["Feature Extraction<br/>(CNN/Transformer)"]

end

subgraph "Modality 2: Genomics"

G["Molecular Sequences<br/>(NGS/VCF)"] --> FE2["Genomic Encoding"]

end

FE1 --> F["Multimodal Fusion Layer"]

FE2 --> F

F --> P["Predictive Neural Network"]

P --> Out["<b>Predictive Foresight</b><br/>Distant Metastasis Prediction"]

subgraph "Pan-Cancer Scope: Multiple Malignancies"

Out

end

style F fill:#fff9c4,stroke:#fbc02d,stroke-width:2px

style Out fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2pxTo understand the complexity of this model, we must define the technical lexicon of modern oncology AI:

- Pan-cancer: Refers to the analysis of multiple different types of cancers simultaneously, identifying common survival patterns across diverse malignancies.

- Multimodal Data: The integration of more than one data modality—in this case, combining High-Resolution Histopathology Images (tissue structure) with Genomics Data (molecular sequences).

- Multimodal Neural Network: A sophisticated deep learning architecture specifically designed to ingest and process multiple data types simultaneously, fusing their insights into a single clinical output.

- Predictive Foresight: By leveraging this multimodal fusion, the model predicts the probability of Distant Metastasis across various cancer types, providing clinicians with a predictive window that single-modality systems cannot achieve.

Prof. Kshitij Jadhav further detailed the broader shifts in this space:

- The Shift to Open Source: The world of clinical AI is moving beyond classical localized CNNs. High-performance, Open Source Multimodal Models are emerging, such as Google’s Med-Gemma—a vision-language model that can process both clinical images and text instructions simultaneously.

- The Integration Benefit: A critical finding in multimodal research is that while analyzing Genomics or Histopathology in isolation may not show statistically significant prognostic differences, their Fusion (Integration) yields results that are highly significant. This mirrors how doctors actually function—never relying on a single test, but integrating clinical notes, images, and labs to reach a decision.

- Path to Personalized Medicine (The 'Holy Grail'): AI is bridging the gap toward the long-promised goal of Personalized Medicine. A key project at Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH)—conducted in Multinational Collaboration with researchers in France and Russia—focuses on Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. The goal is to solve a critical clinical challenge: the administration of high-dosage cytotoxic chemotherapy without a definitive prediction of individual response.

- Beyond Binary Diagnosis: While identifying Reed-Sternberg cells confirms a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s vs. Non-Hodgkin’s, researchers are now looking deeper into Whole Slide Images (WSI).

- Cell-by-Cell Precision: By annotating slides cell-by-cell—identifying Lymphocytes, Neutrophils, Eosinophils, and Basophils—clinicians have fine-tuned open-source models to achieve 80-85% accuracy in cell identification.

- Informed Therapy Selection: This precision allows clinicians to map the Tumor Micro-environment, enabling the prediction of Therapy Response before treatment even begins. This is the "Holy Grail" of oncology—avoiding unnecessary toxicity and directing patients toward the most effective line of therapy from day one.

Decoding the Blueprint: The Role of Genomics & Epigenomics

A foundational pillar of research at KCDH involves understanding human diseases at their most basic level: the DNA, RNA, and the Epigenome.

Figure: The DNA Blueprint—Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G).

Figure: The DNA Blueprint—Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G).

- The Foundation of Personalized Medicine: Personalized medicine is not just about the "average" patient; it is about tailoring treatment to the individual's unique biological landscape. This approach depends heavily on the dual understanding of the Genome (the DNA sequence itself) and the Epigenome (the chemical modifications that control how genes are turned on or off).

- The Molecular Signature: Every disease leaves a signature at the molecular level. By studying the ATCG blueprint alongside epigenetic markers, researchers can identify the exact changes and regulatory shifts that drive specific human diseases.

- From Tangential to Central: While often seen as a specialized field, genomics and epigenomics are increasingly central to digital health. The ability to process and analyze these massive datasets allows for a level of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Precision that was previously impossible.

- Digital Health Integration: At KCDH, the focus is on bridging the gap between molecular research and clinical practice. Integrating these genomic and epigenetic "blueprints" into digital health platforms ensures that the patient's individual biological reality is the primary driver of their longitudinal record.

Single-Cell Resolution: The Future of Precision Oncology

The frontier of genomic research at KCDH has moved beyond bulk tissue analysis to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq). This technology offers an unprecedented resolution into the cellular composition of tumors, allowing researchers to characterize disease at an individual cell level.

- The Methodology: Cellular Barcoding:

- Dissociation: Tissue (e.g., from the liver or brain) is dissociated into individual cells that are physically separated.

- Unique Identity: Each cell is assigned a unique barcode sequence. This barcode is attached to every RNA molecule extracted from that specific cell, ensuring that even after sequencing, the "molecular identity" of the cell is preserved.

- mRNA Quantification (Poly-A Sequencing): The system captures mRNA molecules (identifiable by their poly-A tails), converts them to cDNA, and sequences them via high-throughput sequencers.

- The "Abundance of Differences" Principle:

- Most physiological issues and disease progressions arise from an abundance of specific proteins or protein-producing sequences.

- By comparing normal vs. cancerous samples, clinicians can quantify exactly how much mRNA each cell possesses, identifying the "abundance of differences" (transcriptomic shifts) that drive disease.

- Precision Targeting: Even within a single organ, cancer may only affect specific cell types. scRNA-seq allows researchers to pinpoint these exact cells among the trillions (36+ trillion) in the human body, avoiding the noise of "bulk" analysis.

- Viral Pathogen Detection: Using advanced algorithms, researchers can now extract Viral Pathogen data (e.g., HPV 16, 18, 54) from human-derived RNA sequences, even when the original assay wasn't designed for it. Recent studies identified HPV 16 expression exclusively within specific clusters of infected cells.

- Reproducible Biomarkers: Because biological data is inherently noisy, KCDH develops advanced statistical models to denoise the data and transition from "one-off" observations to reproducible, clinical-grade biomarkers.

Case Study: Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD)

Beyond oncology and acute poisoning, KCDH is addressing one of India's most widespread yet silent health crises: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), increasingly referred to as Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD).

- The Silent Epidemic: An estimated 1 in 3 individuals in India suffers from a fatty liver. Most cases remain undiagnosed because patients are often asymptomatic until the disease is advanced.

- The Diagnostic Gap: Current gold standards for diagnosis—Ultrasound and Fibroscan—are often reserved for symptomatic patients, leaving millions of early-stage cases undetected.

- The AI Goal: "Single-Drop" Diagnostics: The ultimate objective is to develop a diagnostic tool as simple as a glucose or HbA1c test. By identifying robust immune-system biomarkers in the blood that correlate with liver changes, KCDH aims to enable fatty liver detection from a single drop of blood.

- Overcoming Complexity: Immune changes in the liver are notoriously difficult to characterize. Standard methodologies often struggle with the non-reproducibility of biomarkers across different populations. KCDH is leveraging advanced AI algorithms to identify these elusive, reproducible markers, bridging the gap between clinical research and scalable screening.

Federated Learning: Collaboration Without Data Sharing

One of the most significant barriers to clinical AI is the "Data Silo" problem. Prof. Kshitij Jadhav introduced Federated Learning as the definitive solution for privacy-preserving collaboration: - The Dilemma: Multiple hospitals have vast amounts of similar data, but regulatory and ethical barriers prevent them from sharing raw patient records with each other. - The Architecture: In a Federated system, the raw data never leaves the hospital.

graph TD

subgraph "Hospital A (Local)"

DA["Raw Patient Data"] -.-> LA["Local Model A"]

end

subgraph "Hospital B (Local)"

DB["Raw Patient Data"] -.-> LB["Local Model B"]

end

subgraph "Hospital C (Local)"

DC["Raw Patient Data"] -.-> LC["Local Model C"]

end

subgraph "Central Aggregator"

GM["<b>Global Federated Model</b>"]

end

LA -- "Model Parameters Only" --> GM

LB -- "Model Parameters Only" --> GM

LC -- "Model Parameters Only" --> GM

GM -- "Optimized Learnings" --> LA

GM -- "Optimized Learnings" --> LB

GM -- "Optimized Learnings" --> LC-

Case Study: COVID-19 Triage: This approach was scaled for COVID-19 status prediction. By analyzing routine Vitals and Basic Blood Tests across diverse hospital ecosystems, the federated global model achieved significantly higher accuracy than any individual local model. By learning from the "diversity of scenarios" across institutions without ever seeing a single patient's name, Federated Learning proves that privacy is not a barrier to, but a facilitator of, clinical excellence.

-

Balancing AI & Judgment: Clinicians must balance AI-driven decision support with Clinical Judgment and Patient Preferences. AI should be viewed as an "informed second opinion," where the final diagnostic and therapeutic word always rests with the human clinician and the patient's individual autonomy.

- AI Cybersecurity Risks: Integrating public or non-standardized AI models introduces new attack vectors. Secure clinical AI requires private, HIPAA-compliant instances (VPCs) to ensure patient data never leaks into training sets or public domains.

Data Security: At Rest & In Transit

- Data at Rest: Diagnostic reports and medical images must be secured using AES-256 bit Encryption to ensure data remains unreadable if storage media is compromised.

- Data in Transit: Patient data shared with national backbones like ABDM must be protected using TLS 1.3 / SSL to prevent "man-in-the-middle" attacks.

- DMZ (Demilitarized Zones): Acts as a security buffer, allowing external communication (via VPCs) without exposing core clinical databases.

- RBAC (Role-Based Access Control): Ensures that only authorized personnel can access specific pillars of a patient's medical history.

- Compliance & Audit: Regular automated security audits are mandatory to maintain long-term trust in "my hospital data."